Introduction

This paper concerns the connection between the broad questions addressed by the Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government relations (Etkowitz and Leydesdorff, 1995) and its relation to orthodox and heterodox economics with particular emphasis on evolutionary economics. The theory behind the Triple Helix covers much ground which is unfamiliar in economics (particularly cybernetics and phenomenology), and my purpose is to establish connections between its theory of communication and self-organisation and more widely understood evolutionary economic theory represented in the work of Marx, Walros, Veblen, Marshall, Hayek and Schumpeter. I will argue that situating the Triple Helix and its ideas within a richer history of economic thought is to open up a broader stream of critical debate about its techniques and its potential for advancing understanding about socio-economic development.

This paper concerns the connection between the broad questions addressed by the Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government relations (Etkowitz and Leydesdorff, 1995) and its relation to orthodox and heterodox economics with particular emphasis on evolutionary economics. The theory behind the Triple Helix covers much ground which is unfamiliar in economics (particularly cybernetics and phenomenology), and my purpose is to establish connections between its theory of communication and self-organisation and more widely understood evolutionary economic theory represented in the work of Marx, Walros, Veblen, Marshall, Hayek and Schumpeter. I will argue that situating the Triple Helix and its ideas within a richer history of economic thought is to open up a broader stream of critical debate about its techniques and its potential for advancing understanding about socio-economic development.

The Triple Helix of University-Government-Industry relations has become an influential model of economic evolution over the last 20 years. It develops the propositions of evolutionary economics into a set of analytical and empirical practices grounded in the theory of human communication. It is, consequently, extremely ambitious - a fact which has not however prevented it becoming significant in the discourse concerning innovation policy and economic development. For national and international policy-makers, its appeal lies in a promise of empirical techniques which benchmark the vibrancy of innovation in local and national contexts, whilst indicating those areas where regulatory intervention might ameliorate or expand innovative activity. Since policy-makers seek techniques which can make their political task easier, the Triple Helix is attractive. However, in attempting to bridge the gap between policy and theory, and in bringing together a broad range of ideas, the Triple Helix sits awkwardly within the context of mainstream critical economic discourse: it has been championed by a relatively small group of scholars who have specialised in its techniques, whilst there has been limited impact in mainsteam evolutionary economic thinking, or other orthodox and heterodox approaches.

Triple Helix scholarship represents a broad range of theoretical and practical work. It encompasses general analyses of industrial clusters (developing Porter’s (1998) ideas), the economics of innovation, the application of social network analysis, big data analysis, bibliometrics and scientometrics, together with more general sociological approaches. In its totality, the Triple Helix represents not solutions to the problems of economic development, but rather a space for asking interesting questions about economics, innovation, communication and human consciousness.

The paper begins with Hodgson's (1993) typology of evolutionary economics, as a way of presenting the broader picture within which the Triple Helix and its techniques might fit. I then consider the cybernetic ideas behind the Triple Helix and in particular the cybernetics of communication. The use of the formulae from Shannon's information theory are used as an example of how economic dynamics may be studied as communication dynamics. The cybernetic questions frame a discussion about human consciousness in communication - and particularly the study of expectations as it was articulated within the phenomenology of Husserl and Schutz. Finally I focus on some new developments in information theory which focus not on the foreground of information, but on redundancy. In my conclusion, I argue that the analytical focus of the Triple Helix changes the position in Hodgson's typology. In particular, an approach based on routine may be promising for changing the way econometric techniques are deployed more generally.

The paper begins with Hodgson's (1993) typology of evolutionary economics, as a way of presenting the broader picture within which the Triple Helix and its techniques might fit. I then consider the cybernetic ideas behind the Triple Helix and in particular the cybernetics of communication. The use of the formulae from Shannon's information theory are used as an example of how economic dynamics may be studied as communication dynamics. The cybernetic questions frame a discussion about human consciousness in communication - and particularly the study of expectations as it was articulated within the phenomenology of Husserl and Schutz. Finally I focus on some new developments in information theory which focus not on the foreground of information, but on redundancy. In my conclusion, I argue that the analytical focus of the Triple Helix changes the position in Hodgson's typology. In particular, an approach based on routine may be promising for changing the way econometric techniques are deployed more generally.

The Triple Helix and Hodgson's Typology of Evolutionary Economics

Economic evolution is a contested concept. Fundamentally, as Nelson and Winter point out, its purpose is to address the problem of technical change about which adequate explanations are lacking in classical economics. However, the way the emergence of political economy can be understood as evolution clearly depends on the nature of the distinctions that are made as to what it is that is supposed to be evolving, and what the mechanisms of evolution are. There are, of course, a variety of evolutionary models, with important differences separating the ideas of Lamarck, Darwin, Spencer and Huxley. It is then of little surprise to find that there are a variety of evolutionary economic models, each subscribing to different evolutionary ideas. These have been summarised as a typology of evolutionary economics by Hodgson, who whilst accepting the deficiencies of this kind of typology, defends the approach as a way of asking critical questions about evolutionary economics.

Dividing evolutionary economics into two sub-categories of 'Developmental' (Type 1) and 'Genetic' (Type 2), Hodgson first separates Marx's work (which is often characterised as a variety of social Darwinism) from the work of those economists belonging to the classical, Austrian, neoclassical and institutionalist schools. Marxist accounts in focusing on a materialist ontology and dialectic of development tend not to identify processes of selection or 'germs' for development, instead presenting a series of unfolding stages of political struggle. Those accounts which do seek to identify selection mechanisms and organic fundamentals fall into Type 2 (Genetic). Within this category, the principal distinction is between those mechanisms which describe economy as a single 'organism' (2.1 Ontogeny), and those that describe economy as the development of a species (2.2 Phylogeny). For ontogenetic changes, there is a further distinction between those explanations which describe a continuous dynamic (for example, Smith's invisible hand (1759; 1776) or Walros's (1877) equilibria), and those mechanisms which describe a punctuated, but nevertheless continuous, process of which Schumpeter's (1942) 'creative destruction' is the classic example. On the phylogenetic side, the issue is whether evolutionary development of a species attains some kind of consummation, following rules whereby an evolved species can be predicted based on the fitness of earlier stages of development. For example, Spencerian 'survival of the fittest' can be seen in Hayek's (1960) 'spontaneous order', whilst Veblen's institutional emergence shows no kind of rule for determining evolved states from previous states. In first examining this typology, the obvious question is "Where might the Triple Helix fit?"

Whilst one might argue with the specific categorisations in Hodgson's typology, there are clear distinctions between ways of thinking about economic development, and for all their differences, each of the economists represented has something specific to say about evolution. Whilst our modern conception stems from Nelson and Winter and their desire to account for technical change, the origins of an evolutionary and biological economics go back further. At the end of the 19th century Thorstein Veblen asked “Why is Economics not an evolutionary science?” (Veblen, 1898). Alfred Marshall's major contributions to neoclassical economics were framed by his latent ambition to grapple with evolutionary dynamics. He states in the preface to his “Principles of Economics” in 1890, “The Mecca for the economist in an economic biology” (Marshall, 1890). Veblen felt that the orthodox classical model could not account for economic development as a living thing, and each sought to characterise developmental processes in economic theorising. In particular, Veblen saw the evolutionary metaphor as crucial to the understanding of the processes of technological development in a capitalist economy. Critiquing Marshall's neoclassicism, Veblen considered that evolutionary ideas should be embraced by the economist from the start, rather that attempting first to define static equilibrium models as both Marshall and later Pigou did. With Veblen's death in 1929, little development in the evolutionary idea occurred until Nelson and Winter's "An evolutionary theory of economic change" appeared in 1982.

The explanatory challenge faced by evolutionary economics is that of technical change and its emergent effects (Nelson and Winter, 1982). Technical change was not just a change in the material and technological fabric of society, it was a change in the capabilities of human beings. Veblen pointed out, technical change meant that human learning and education was fundamentally in the economic mix. Thus the evolutionary problem in economics produces a number of areas of interest: biology, learning, technology and social organisation.

Whilst one might argue with the specific categorisations in Hodgson's typology, there are clear distinctions between ways of thinking about economic development, and for all their differences, each of the economists represented has something specific to say about evolution. Whilst our modern conception stems from Nelson and Winter and their desire to account for technical change, the origins of an evolutionary and biological economics go back further. At the end of the 19th century Thorstein Veblen asked “Why is Economics not an evolutionary science?” (Veblen, 1898). Alfred Marshall's major contributions to neoclassical economics were framed by his latent ambition to grapple with evolutionary dynamics. He states in the preface to his “Principles of Economics” in 1890, “The Mecca for the economist in an economic biology” (Marshall, 1890). Veblen felt that the orthodox classical model could not account for economic development as a living thing, and each sought to characterise developmental processes in economic theorising. In particular, Veblen saw the evolutionary metaphor as crucial to the understanding of the processes of technological development in a capitalist economy. Critiquing Marshall's neoclassicism, Veblen considered that evolutionary ideas should be embraced by the economist from the start, rather that attempting first to define static equilibrium models as both Marshall and later Pigou did. With Veblen's death in 1929, little development in the evolutionary idea occurred until Nelson and Winter's "An evolutionary theory of economic change" appeared in 1982.

The explanatory challenge faced by evolutionary economics is that of technical change and its emergent effects (Nelson and Winter, 1982). Technical change was not just a change in the material and technological fabric of society, it was a change in the capabilities of human beings. Veblen pointed out, technical change meant that human learning and education was fundamentally in the economic mix. Thus the evolutionary problem in economics produces a number of areas of interest: biology, learning, technology and social organisation.

Few explanatory frameworks offer a coherent approach which encompasses human learning, biology, technology and economic and social organisation. In the late 1940s, the Macy conferences were called in New York the aftermath of technological developments during World War 2 as a platform for discussing "Feedback Mechanisms and Circular Causal Systems in Biological and Social Systems". Shortly after, the term 'cybernetics' became the name for this inter-disciplinary investigation. Whilst many ideas from cybernetics became influential in economics (in particular, Von Neumann and Morgenstern's game theory), the cybernetic heritage in economics is largely forgotten. Yet cybernetics remains a powerful way of thinking about a wide variety of phenomena in the world, creating what Gordon Pask argued were ‘defensible metaphors’. With regard to the Triple Helix, it provides powerful tools for finding a path through the complex inter-relationships between communication, learning, technology and organisation.

Cybernetics in the Triple Helix

The relationship between communication and control has been central to cybernetics from the beginning. Norbert Wiener's original book on cybernetics was sub-titled "Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine" (Wiener, 1948), and with these twin concepts cybernetics applied its metaphors to phenomena ranging from psychiatry, philosophy, biology, computer science, anthropology, ethology and sociology. This broad range of applicability of cybernetic ideas necessitated a balancing of the need for holistic explanation with a fundamental ontological reductionism whereby all relevant phenomena could be seen through the lens of 'communication and control'. Cybernetic ontology shares much with the sceptical ontology of David Hume, who had argued that there are no real causes or necessary regularities in nature: such regularities and causes as they are determined to exist are constructed through the communications of scientists (Hume, 1748). Cybernetics concerns itself with studying communication and control within these epistemological processes, thus reframing scientific understanding in the context of communication and control.

Cybernetics possesses key concepts in the characterisation of communication and control. Cybernetic mechanisms are mechanisms which display circularity in their operations (an aspect of which may be called 'feedback'), and the dynamics of circularity produce phenomena such as "homeostasis" (the steady state dynamic), "variety" (a measure of complexity) and "entropy" (a measure of disorder). Building on these concepts are some fundamental principles. Most famously, Ross Ashby identified a Law concerning control: the "Law of Requisite Variety" (Ashby, 1958). Ashby's law states that a complex system of variety x can only be controlled by another complex system with the same or greater variety: colloquially, it states “Only variety can absorb variety”. It takes one football team to absorb the variety of another football team.

Ashby’s law concerns the interaction of complex mechanisms (he produced a machine called the 'homeostat' to demonstrate it), but can be looked at from a different angle. A machine which generates and transmits a message can exist in the number of states that are required to generate the complexity of the message. For a machine to successfully receive such a message, it must also be able to exist in at least the same number of states. The channel connecting the two machines must be able to transmit the variation in the states of the machines. Thus, the flip-side of Ashby produces a diagram as was presented by Claude Shannon (Shannon and Weaver, 1948) in his information theory: the relationship between sender and receiver is homeostatic if communication is successful. A more powerful consequence of this is that messages (information) is tied up with the interactions of machines with variety.

Information Theory and the Triple Helix Measurements

The Triple Helix situates itself with the effort to reconcile information theory with a broader empirical approach to human communication and development. Shannon’s information theory has been remarkably successful in helping technologists create powerful algorithms which now comprise major parts of the internet infrastructure. Techniques for compression and encryption have facilitated search and security respectively, and the consequently vast amounts of data are subject to analyses and data mining which too draws heavily on Shannon's formulae. Much contemporary analytical work on 'big data' is focused on analysing semantics and the intentions of agents, and whilst Shannon himself discounted the possibility of his theory being applicable to human communication situations, evidence from these analyses appear to suggest that the applicability of his formulae for human communication is not infeasible.

Behind Shannon's formulae are the concepts of 'surprise' and 'confirmation' (von Weizsäcker, 1974). Both of these are anthropocentric concepts which suggest a human dimension even when Shannon discusses the communication between abstract machines. Shannon's empirical techniques aim to quantify the surprisingness of communications. He measures average surprise as the sum of the logarithms of probabilities of communication by adapting Boltzmann's formula for thermodynamic entropy:

Behind Shannon's formulae are the concepts of 'surprise' and 'confirmation' (von Weizsäcker, 1974). Both of these are anthropocentric concepts which suggest a human dimension even when Shannon discusses the communication between abstract machines. Shannon's empirical techniques aim to quantify the surprisingness of communications. He measures average surprise as the sum of the logarithms of probabilities of communication by adapting Boltzmann's formula for thermodynamic entropy:

The probability of surprising event is small (otherwise it would not be surprising!), but its logarithm is a large negative number. Conversely, the probability of an unsurprising event is close to 1, but its logarithm is a small negative number. Adding the logarithms of the probabilities of each element in a message weighted by their probabilities results in a measure of the average surprisingness of the content of the message. By using logarithms to base-2 this provides a useful measure of the amount of information expressed in the number of bits required to carry this information.

In addition to calculating the information in a message, it is also possible to calculate the exhanged between sender and receiver. Recalling that the complexity of the receiver relates to the complexity of the sender, the mutual Information between them must relate to the Shannon entropies at each end in a two-way communication. If we have a sender, A and a receiver, B, then the mutual information between A and B can be calculated as:

In addition to calculating the information in a message, it is also possible to calculate the exhanged between sender and receiver. Recalling that the complexity of the receiver relates to the complexity of the sender, the mutual Information between them must relate to the Shannon entropies at each end in a two-way communication. If we have a sender, A and a receiver, B, then the mutual information between A and B can be calculated as:

In the three dimensions that the Triple Helix concerns itself with, this equation is:

Human interaction situations are far more complex than the dynamics of communication described in Shannon's diagram. Human dynamics are multidimensional and rich. The surprisingness in human communications is not simply a function of transmission and reception, but of continual learning and reflexivity. Each individual acquires new knowledge, moving in different networks, and as a result there is an ebb-and-flow of the mutual information between people. If we were to write down every utterance everyone made with everyone else and apply Shannon's formulae to these communications, then the dynamics of the interactions between participants and the shifting patterns of the information they share could be studied.

Today an increasing amount of communication is carried online making this communication available for analysis. Whilst it remains only a small fraction of our daily utterances, it still represents a vast amount of communication, and some of this communication is clearly organised into professional discourses. This presents an analytical opportunity from where what is often referred to as the 'knowledge-economy' becomes tractable. In the diagram below, for example, the discourse of scientists is generally carried in academic journals (represented as 'knowledge'), the discourse of politicians is carried in national and regional policy documents (represented as 'geography') and the discourse of industry can be represented in such documents as patent applications (represented as 'economy'). Given this compartmentalisation of discourse, it becomes possible to utilise the equations for calculating mutual information dynamics between the different dimensions.

Leydesdorff explains the simplest way of doing this based on searches for the key terms "University", "Industry" and "Government" (Leydesdorff, 2006). Whilst somewhat crude as an example, it demonstrates the principle. With search engines, it is possible to identify the number of documents containing the word "University". The same may be performed for the other keywords. It is also possible to find the number of documents containing pairs of words. In order to ascertain the probabilities of these words online, we also need to know the number of documents not containing any of them. This provides enough information to calculate the probabilities of each term and each pair of terms, and therefore Shannon's H can be calculated in each case. Using the formula for calculating mutual information in three dimensions, a number can be produced which indicates the mutual information between the three components.

If this data is collected and calculated longitudinally then the mutual information measure can act as an indicator of the emerging dynamics of mutual information between different discourses over time. Furthermore, the searches for key terms can be delimited to specific countries or regions, and comparisons made between regional and national performance and correlations made between figures for mutual information and other economic data.

The key question then is, What does this tell us? Whilst it is tempting to see the Triple Helix as an indicator (or even a predictor) of innovation, it is important not to get carried away. The Triple Helix measurements are indicators of possible ways that human beings interact - it is an indication of what might be between us, yet there is much that remains abstract and obscure. Beyond the possibilities of national economic comparison and the potential for identifying interventions, the Triple Helix connects an analysis of communication with insight into the spiritual life and intentionality of individuals and their motivations. In making this connection it begins to make tractable a number of key questions which reflect back on Marshall's "Mecca" of an economic biology by asking:

- To what extent do communications and mutual information measurements reflect the internal bio-psychosocial organisation of individuals?

- To what extent might the shifting patterns of mutual information reveal transformations in individual agency, cognition, skill, competency and technological adeptness?

Phenomenology and Communication

One of the central problems of measuring mutual information in published communications on the internet and elsewhere is that human communication is not only verbal. Empathy, compassion and tacit knowledge all play a powerful role in human communication processes, indeed without these tacit dimensions, human communication might not be possible at all. The reflexive processes of human communication have been extensively studied by phenomenologists from the late 19th century onwards. Spearheaded by Husserl, questions of personhood, identity and meaning became framed as a study of social intercourse which Husserl called 'intersubjectivity' (Husserl, 1931). In the work of Parsons (1937), Luhmann (1995) and Varela (Varela, Thompson and Rosch, 1993) in the later 20th century, phenomenological insights gained a systems-oriented expression which can be seen to integrate with the systems perspective of the Triple Helix. However, the extent to which a systems-oriented phenomenology is faithful to Husserl's original inquiry - and particularly Husserl's famous concern about the "mathematicisation of nature" (Husserl, 1954) - is contested.

Husserl's theory of Intersubjectivity provides a rich territory for debate amongst his followers. There are important and subtle differences between the perspectives of Scheler, Merleau-Ponty and (perhaps most importantly) Schutz. Husserl’s question about the ‘inter-subjective’ concerned the expression of empathy, compassion and intuition about one another's experiences. Central to his conception was the idea that the world manifests itself to humans as a ‘horizon of meanings’: this is the set of expectations about the world through which experience is coordinated. Schutz (1975) explains Husserl's position on intersubjectivity by quoting him saying "the experiences of others manifest themselves to us" explaining that "we apprehend them by virtue of the fact that they find bodily expression." This bodily expression entails, Husserl argues, a shared experience of the world but one which is constructed through experience. Schutz argues that Husserl's "painfully puzzling question" is "how another psychophysical ego comes to be constituted in my ego, since it is essentially impossible to experience mental contents pertaining to other persons in actual originarity." For his part, Schutz argues against both Husserl's transcendental method, which he feels ignores the sociological dimension, and to his explanation of intersubjectivity whereby one person comes to know another through what Husserl calls 'appresentation'. On this latter point, Schutz points out (along with Scheler and Merleau-Ponty) that a person's body is not known to themselves in the same way that the Other's body becomes known to them. Such problems dominated Schutz's own thinking about intersubjectivity.

Husserl's theory of Intersubjectivity provides a rich territory for debate amongst his followers. There are important and subtle differences between the perspectives of Scheler, Merleau-Ponty and (perhaps most importantly) Schutz. Husserl’s question about the ‘inter-subjective’ concerned the expression of empathy, compassion and intuition about one another's experiences. Central to his conception was the idea that the world manifests itself to humans as a ‘horizon of meanings’: this is the set of expectations about the world through which experience is coordinated. Schutz (1975) explains Husserl's position on intersubjectivity by quoting him saying "the experiences of others manifest themselves to us" explaining that "we apprehend them by virtue of the fact that they find bodily expression." This bodily expression entails, Husserl argues, a shared experience of the world but one which is constructed through experience. Schutz argues that Husserl's "painfully puzzling question" is "how another psychophysical ego comes to be constituted in my ego, since it is essentially impossible to experience mental contents pertaining to other persons in actual originarity." For his part, Schutz argues against both Husserl's transcendental method, which he feels ignores the sociological dimension, and to his explanation of intersubjectivity whereby one person comes to know another through what Husserl calls 'appresentation'. On this latter point, Schutz points out (along with Scheler and Merleau-Ponty) that a person's body is not known to themselves in the same way that the Other's body becomes known to them. Such problems dominated Schutz's own thinking about intersubjectivity.

Talcott Parsons had a correspondence with Schutz following an invitation to Schutz to review Parsons’s “The structure of social action” (Grathoff, 1979). This was a difficult of exchange of ideas between the two, as Parsons’ functionalism made Schutz uneasy, just as Schutz’s phenomenological reflections appeared to irritate Parson. Within Parsons's own social systems theory, an account of intersubjectivity became reframed as a dynamic of expectations between an "ego" and an "alter". Parsons articulates the idea of a 'double-contingency' of communication whereby the expectations of communication between ego and alter-ego are coordinated. Parsons double-contingency was later developed by Niklass Luhmann who made the connection between Shannon-type probabilistic selections of 'information', 'meaning' and 'utterance' between ego and alter-ego. Luhmann's multi-level selections provided a functionalist model of intersubjectivity with considerable (and influential) explanatory power, but with some sacrifice of the original subtlety of Husserl's and Schutz's thought. The deficiencies of the theory have been keenly observed by Habermas (1987, quoted in Leydesdorff, 2006) who points out that: "subject-centred reason is replaced by systems rationality. As a result, the critique of reason carried out as a critique of metaphysics and a critique of power […] is deprived of its object. [...] it replaces metaphysical background convictions with metabiological ones." In other words, the Kantian idealism of the 'transcendental subject' remains in the form of network dynamics, despite the attempt to describe a transpersonal intersubjective realm of communication.

In Triple Helix analysis, the question is whether analytical purchase can be gained on the intersubjective realm by analysing mutual information. In other words, do the shifts in mutual information indicate shifts in intersubjective expectations? In Luhmann's terms, this would be to uncover an ‘imprint of meaning’ in the interactions between agents in a network. The systems theoretical study of expectations has produced a variety of models of systems which contain models of themselves and anticipate their future. These 'anticipatory systems' have been articulated in the work of Rosen (1985), Beer (1995), and Dubois (1998), all contributing to an understanding of reflexive experience which, in Hayles's words, is "that moment by which that has been made to generate a system is made, by a changed perspective, to become part of the system it generates." (Hayles, 1999)

Anticipatory system dynamics provides a way of conceiving of consciousness as a simultaneous process of coordination between the flow of events as relations over time, the conscious positioning of utterances in a meaningful context, and the reflexive process of re-interpreting and translating past events to project possible futures. Whilst deeper critical exploration is required as to what is lost in translation between the systems theoretical phenomenology and Husserl and Schutz's intersubjectivity, the systems-theoretical perspective does indicate an opportunity to unite the spiritual forces of conscious life and learning with an empirical approach, and provides an opportunity to re-examine the aspirations of evolutionary economists.

Anticipatory system dynamics provides a way of conceiving of consciousness as a simultaneous process of coordination between the flow of events as relations over time, the conscious positioning of utterances in a meaningful context, and the reflexive process of re-interpreting and translating past events to project possible futures. Whilst deeper critical exploration is required as to what is lost in translation between the systems theoretical phenomenology and Husserl and Schutz's intersubjectivity, the systems-theoretical perspective does indicate an opportunity to unite the spiritual forces of conscious life and learning with an empirical approach, and provides an opportunity to re-examine the aspirations of evolutionary economists.

In the Triple Helix, Leydesdorff argues that the equations of Dubois (1998) can be used to simulate the dynamics in the knowledge economy. Central to this conception is the simultaneous dynamics of functions working in the flow of time which he calls:

- recursive functions as adaptation to events, expressed as the logistic map:

- incursive functions as a self-organising dynamic within individual discourses

- a hyperincursive function which works reflexively against the flow of time.

The interaction between these equations produces a dynamic which oscillates between periods of co-evolution and self-organisation among different discourses, and periodic global reorganisation in terms of cultural selections.

Having reached this point, it is important to be reminded of the assumptions made in the theoretical background of the Triple Helix and its possible problems:

- Intersubjectivity and communication

- Expectation and meaning

- Mutual Information and reflexivity

- Metrics, policy interventions and assumed effects

Behind these problems are fundamental questions about the possibility of analysis, determinism and free will in a society driven by metrics. There remain questions about abstraction, modelling and reality which have plagued economics since Menger's (and later, Hayek's) critique of formalism, and particular questions about the Triple Helix's relationship to econometrics. Most importantly we have to ask an ontological question: What would a world be like in which this theory was correct? In what way would that world be different from the world that we see around every day?

Routine and Redundancy: Some recent Developments in the Theory of Information

The Triple Helix cannot address all these concerns. It remains a functionalist approach to evolutionary economics, not least because it sits upon cybernetics which itself is functionalist. It is also probably fair to say that cybernetics has a principal weakness – at least at the current time – that it is insufficiently self-critical. The Triple Helix is vulnerable to those critics of abstraction and econometrics, including Menger (1971), Hayek (1996) and more recently Lawson (2002) and Hodgson (2005). Its problems stem from the fact that the Triple Helix idealises its categories: there are no real people, no real universities, no real industries and no real governments. This is partly a problem with Luhmann’s theory, and ultimately means that Habermas's contention that the systems theoretical perspective denies a space for critiquing power relations is a serious challenge.

The Triple Helix's approach to information and meaning situates it with a parallel critical discourse about information. Recent attempts to define a coherent theory of information including those of Floridi (2012), Mingers (2014), Deacon (2012), Ulanowicz (2009) and others have had to grapple with the tendency for information theory to become a theory of agency, thus losing its essential status as something which is relational. Within the various philosophical approaches to information, Shannon's formulae remain the principal means of doing empirical work.

Despite the deficiencies of the Triple Helix, its concrete focus on data concerning development, communication, human learning and organisation sit at the heart of both the concerns of information theorists and economists. Among the economists, both the Austrian school and neo-Keynesians like Stiglitz see the analysis of information playing a fundamental role in economic theory. Stiglitz (2014) has recently explored the relationship between learning and broader economic dynamics. In an age of giant internet corporations and social software that anxieties about privacy, liberty, national security, cyber-warfare, Wikileaks, Edward Snowdon, and so on that information impacts all of our lives.

The Triple Helix's approach to information and meaning situates it with a parallel critical discourse about information. Recent attempts to define a coherent theory of information including those of Floridi (2012), Mingers (2014), Deacon (2012), Ulanowicz (2009) and others have had to grapple with the tendency for information theory to become a theory of agency, thus losing its essential status as something which is relational. Within the various philosophical approaches to information, Shannon's formulae remain the principal means of doing empirical work.

Despite the deficiencies of the Triple Helix, its concrete focus on data concerning development, communication, human learning and organisation sit at the heart of both the concerns of information theorists and economists. Among the economists, both the Austrian school and neo-Keynesians like Stiglitz see the analysis of information playing a fundamental role in economic theory. Stiglitz (2014) has recently explored the relationship between learning and broader economic dynamics. In an age of giant internet corporations and social software that anxieties about privacy, liberty, national security, cyber-warfare, Wikileaks, Edward Snowdon, and so on that information impacts all of our lives.

With these twin discourses (economics and information) both focusing on similar problems, we can return to the original question as to where the Triple Helix might fit within evolutionary economics. When Veblen considered the question of why economics was not an evolutionary science, he argued that the most important aspect of innovation was the routine of workers. This is a point echoed by Nelson and Winter and in sociology with the "interaction rituals" studied by Collins. In each case, it appears that there is a desire to turn the analytical focus onto the background of practice: that which in information theory terms, is termed 'redundancy'. In the philosophy of information, there has been a similar move towards considering the importance of redundancy. Ulanowicz, for example, argues that "the most important thing about information is not information", whilst many years earlier, Bateson argued in a letter to John Lilly that "What I have tried to do is to turn information theory upside down to make what the engineers call 'redundancy' [coding syntax ] but I call 'pattern' into the primary phenomenon". Deacon presents a theory of information in which redundancy is seen as constraint or absence, and this this serves as an autocatalytic process extending from the emergence of biological development to meaning. Ulanowicz echoes a similar ambition to regard "not information", or what he calls 'flexibility' as an autocatalytic process which counterbalances the dynamics of homeostasis.

Redundancy in information theory is a somewhat ambiguous term. It operates as the background to selection, where selection is constrained by various forms of repetition (thus making a selection more likely). In language for example, grammar performs this function. Such repetitions can be viewed as unexplored pathways which lead to similar places - what McCulloch calls the "redundancy of potential command" (see Beer): for every selection of a meaning, a number of similar but different descriptions of how to articulate the same thing are present. Routine represents habits of selection: whether it is the selection of letters to form words, words to form grammatical sentences, and so on. Habits are established whereby many options of expression are not chosen, rendering those unchosen options redundant. At an economic level, habits of selection in consumer behaviour, or in industrial production, or in educational practice, or training similarly entail a background of unchosen options. The habits of selection in an economy change: the constraints of the redundant options shift so that one option may cease to be redundant. Veblen articulated the view that "idle curiosity" was at the root of innovation. Reinterpreting this, an innovative act is one of saying "Why not do x instead?" where x always existed, but was never selected. Artists do this all the time.

Redundancy in information theory is a somewhat ambiguous term. It operates as the background to selection, where selection is constrained by various forms of repetition (thus making a selection more likely). In language for example, grammar performs this function. Such repetitions can be viewed as unexplored pathways which lead to similar places - what McCulloch calls the "redundancy of potential command" (see Beer): for every selection of a meaning, a number of similar but different descriptions of how to articulate the same thing are present. Routine represents habits of selection: whether it is the selection of letters to form words, words to form grammatical sentences, and so on. Habits are established whereby many options of expression are not chosen, rendering those unchosen options redundant. At an economic level, habits of selection in consumer behaviour, or in industrial production, or in educational practice, or training similarly entail a background of unchosen options. The habits of selection in an economy change: the constraints of the redundant options shift so that one option may cease to be redundant. Veblen articulated the view that "idle curiosity" was at the root of innovation. Reinterpreting this, an innovative act is one of saying "Why not do x instead?" where x always existed, but was never selected. Artists do this all the time.

Triple Helix metrics articulate a causal connection between mutual information and economic development. The positive presentation of this connection suggests that mutual information determines innovation. However, the exogenous variables surrounding innovation processes (particularly Veblen's 'idle curiosity') make a determinative causal connection appear a hasty conclusion. However, rather than deterministic approach, it is also possible to argue that innovation is constrained by communication. This is a rather less problematic proposition. Recalling Veblen's arguments about routine, this suggests that analysis of redundancies as constraints on practice provides a way in which empirical analysis can be an invitation to inquiry about the conditions for innovation, rather than the source of a deterministic solution.

The issue as to whether redundancies or mutual information are inspected bears upon where the Triple Helix might be located in Hodgson's typology. Viewed deterministically through the lens of mutual information, Triple Helix optimal situations might be envisaged within communication dynamics which suggest a punctuated ontogenetic approach closely in line with Schumpeter's theory: type 2.12. The economy is treated as a whole system, whose dynamics are sporadically punctuated by moments of "creative destruction". However, if constraints are the principal focus through an analysis of redundancy, then the Triple Helix opens up questions which are more in line with Veblen's institutionalism and his interest in routine: type 2.22.

Veblen's economics presents a rich ecological picture of institutions and society, although it has been criticised for a lack of rigour and systematication. With a constraint-oriented analysis of communication, an analytical context can be created for deeper inspection of Veblen's assertions. Recent developments in statistical ecology support the idea of analysis of constraints as a index of the fecundity of an economy. Ulanowicz's work on biological ecosystems balances measurement of mutual information with the dissipative dynamics associated with energy lost to the environment. Ulanowicz has sought to understand growth patterns in terms of the interplay between homeostatic processes of mutual information and autocatalytic processes which create redundant 'flexibilities'. With mutual information high and flexibility low, an ecosystem is highly efficient but brittle; with mutual information low and flexibility high, there is a risk of disorder. Deacon has expressed similar ideas, highlighting the difference between orthagrade forces and contragrade forces producing autocatalytic effect that he calls 'autogenesis'.

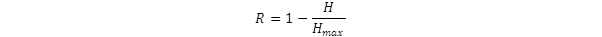

At a more technical level of Shannon's equations, both Ulanowicz and Leydesdorff and Ivanova have attempted to grapple with the problem of analysing redundancies. Most recently, Leydesdorff and Ivanova (2014) have shifted the focus within the Triple Helix towards the measurement of mutual redundancy rather than mutual information. Redundancies can be calculated using the inverse of Shannon's entropy measure,

Leydesdorff and Ivanova explain that the substitution of the measurement of mutual redundancy for mutual information has the advantage of addressing a long-standing problem within Shannon's equations for mutual information in multiple dimensions, studied first by Ashby and later, Krippendorff. However, the focus on mutual redundancies also shifts the analytical focus onto the background constraints of communication. Using a different approach critical of Shannon's original formulae, Ulanowicz has also attempted to examine redundancies of communication. Ulanowicz points out that Shannon's H encompasses the two concepts of 'surprise' and 'confirmation' and that these two concepts should be separated. With a healthy variety of techniques being employed, a rich seam of empirical activity focusing on constraints in economics is opening up.

The issue as to whether redundancies or mutual information are inspected bears upon where the Triple Helix might be located in Hodgson's typology. Viewed deterministically through the lens of mutual information, Triple Helix optimal situations might be envisaged within communication dynamics which suggest a punctuated ontogenetic approach closely in line with Schumpeter's theory: type 2.12. The economy is treated as a whole system, whose dynamics are sporadically punctuated by moments of "creative destruction". However, if constraints are the principal focus through an analysis of redundancy, then the Triple Helix opens up questions which are more in line with Veblen's institutionalism and his interest in routine: type 2.22.

Veblen's economics presents a rich ecological picture of institutions and society, although it has been criticised for a lack of rigour and systematication. With a constraint-oriented analysis of communication, an analytical context can be created for deeper inspection of Veblen's assertions. Recent developments in statistical ecology support the idea of analysis of constraints as a index of the fecundity of an economy. Ulanowicz's work on biological ecosystems balances measurement of mutual information with the dissipative dynamics associated with energy lost to the environment. Ulanowicz has sought to understand growth patterns in terms of the interplay between homeostatic processes of mutual information and autocatalytic processes which create redundant 'flexibilities'. With mutual information high and flexibility low, an ecosystem is highly efficient but brittle; with mutual information low and flexibility high, there is a risk of disorder. Deacon has expressed similar ideas, highlighting the difference between orthagrade forces and contragrade forces producing autocatalytic effect that he calls 'autogenesis'.

At a more technical level of Shannon's equations, both Ulanowicz and Leydesdorff and Ivanova have attempted to grapple with the problem of analysing redundancies. Most recently, Leydesdorff and Ivanova (2014) have shifted the focus within the Triple Helix towards the measurement of mutual redundancy rather than mutual information. Redundancies can be calculated using the inverse of Shannon's entropy measure,

Leydesdorff and Ivanova explain that the substitution of the measurement of mutual redundancy for mutual information has the advantage of addressing a long-standing problem within Shannon's equations for mutual information in multiple dimensions, studied first by Ashby and later, Krippendorff. However, the focus on mutual redundancies also shifts the analytical focus onto the background constraints of communication. Using a different approach critical of Shannon's original formulae, Ulanowicz has also attempted to examine redundancies of communication. Ulanowicz points out that Shannon's H encompasses the two concepts of 'surprise' and 'confirmation' and that these two concepts should be separated. With a healthy variety of techniques being employed, a rich seam of empirical activity focusing on constraints in economics is opening up.

Conclusion: A critical perspective of the Triple Helix

My original question was, Where does the Triple Helix fit in evolutionary economics? In responding to this, it appears that the Triple Helix falls into Hodgson's Type 2: Genetic. However, beyond this categorisation, it depends on the analytical focus with which the Triple Helix is approached. If it is approached as a means of calculating knowledge dynamics as an indicator of innovation capacity, the Triple Helix is Schumpeterian, representing a punctuated continuity which is ontogenetic. However, if the focus turns to the background constraints of innovation, the Triple Helix focuses more on routine and redundancy and becomes more Veblenian: a phylogenetic approach which is non-consummatory. It is clear that the Triple Helix is not consummatory (thus unlike Hayek's 'Spontaneous order'), and it is unlike the continual dynamics of Smith or Walros. It is also not Marxist.

Naturally, further inspection of these positions will invite deeper debate, and this should be welcomed. The advantage of attempting to situate the Triple Helix is to invite debate from other more established economic schools of thought, and highlights the value of the Triple Helix as a space for debate about theory and socioeconomic empiricism. The Triple Helix's value does not lie in any kind of slavish adoption of its formulae, but in:

Naturally, further inspection of these positions will invite deeper debate, and this should be welcomed. The advantage of attempting to situate the Triple Helix is to invite debate from other more established economic schools of thought, and highlights the value of the Triple Helix as a space for debate about theory and socioeconomic empiricism. The Triple Helix's value does not lie in any kind of slavish adoption of its formulae, but in:

- providing a bridge between evolutionary economics, neoclassical economics and other heterodox approaches, allowing for a rich engagement from a number of perspectives;

- providing an opportunity to re-examine empirical approaches – particularly those of neoclassical econometrics;

- opening up the critique of information to neoclassical and neo-Keynesian economics, where information is taken as a given without examining its nature;

- bringing into focus the need to consider issues of consciousness, communication, learning, technology and development;

- making the connection between a critical economic discourse, it reconnects cybernetic thinking to a critical and empirical stream of activity.

Most importantly, the Triple Helix represents an invitation to rethink the nature of information in evolutionary economic processes. It points towards one of the most exciting areas of discourse today, and promises opportunities to marry philosophical debate with practical empirical activity in pursuit of establishing a more effective socio-economic empiricism and political development.

Bibliography

Ashby, R (1958) Requisite Variety and its implications for the control of complex systems, Cybernetica (Namur) Vo1 1, No 2,

Beer, S (1995) Brain of the Firm – 2nd Edition Wiley

Dubois, D. M. (1998). Computing Anticipatory Systems with Incursion and Hyperincursion. In D. M. Dubois (Ed.), Computing Anticipatory Systems, CASYS-First International Conference (Vol. 437, pp. 3-29). Woodbury, NY: American Institute of Physics.

Etzkowitz, H., Leydesdorff, L. (1995). The Triple Helix---University-Industry-Government Relations: A Laboratory for Knowledge-Based Economic Development. EASST Review 14, 14-19.

Grathoff, R (1979) The Theory of Social Action: The Correspondence of Alfred Schutz and Talcott Parsons by Richard Grathoff

Habermas, J (1987) Excursus on Luhmann’s Appropriation of the Philosophy of the Subject through Systems Theory. In The philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twoelve Letures, pp 368-85.

Hayek, F (1960) The constitution of Liberty, Routledge

Hayek, F (1996) Individualism and Economic Order, Routledge

Hodgson, G (1993) Economics and Evolution: Bringing Life back into Economics, Polity Press

Hodgson, G (2005) On the problem of formalism in Economics, in Economics in the Shadows of Darwin and Marx: Essays on Institutional and Evolutionary Themes, Ch 7

Hume, D (1748) An Enquiry concerning Human understanding

Husserl, E (1931) Cartesian Meditations

Husserl, E (1954) The crisis in the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology

Lawson, T (1999) Economics and Reality, Routledge

Leydesdorff, L (2006) The Knowledge-based Economy: Modelled, Measured, Simulated Universal Publishers

Leydesdorff, L; Ivanova, I (2014) Mutual Redundancies in Inter-human Communication Systems:

Steps Towards a Calculus of Processing Meaning, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology

Luhmann, N (1995) Social Systems

Parsons, T (1937) The structure of Social Action

Porter, Michael (2000) Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy Economic Development Quarterly, vol 14, no.1, pp 15-34

Marshall, A (1890) Principles of Economics

Mingers, J (2014) – Systems thinking, Critical Realism and Philosophy: A Confluence of Ideas

Nelson, R; Winter, S (1982) An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change Harvard University Press

Rosen, R. (1985). Anticipatory Systems: Philosophical, mathematical and methodological foundations. Oxford, etc.: Pergamon Press.

Schumpeter (1942) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy

Shannon, C; Weaver, W (1948) A Mathematical Theory of Communication

Schutz, (1975) The Problem of Transcendental Intersubjectivity in Husserl In Collected Writings, Vol III.

Smith (1759) Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith (1776) The Wealth of Nations

Stiglitz (2014) Creating A Learning Society: A new approach to growth, development and Social Progress

Veblen, T (1898) Why is economics not an evolutionary science?

Von Wiesacker, E (1974) Erstmaligkeit und Bestätigung als Komponenten der Pragmatischen Information. In Offene Systeme: Band I. Beiträge zur Zeitstruktur von Information, Entropie und Evolution, von Weizsäcker, E., Ed.; Klett-Cotta: Stuttgart, Germany, pp. 82-113.

Walros (1877) Elements of Pure Economics

No comments:

Post a Comment