Logic is a powerful subject: to reason differently about the world is to change it. And perhaps to reason differently about education as a way of changing it is a start to reason differently about the world. Our reasoning is fundamentally binary: we inhabit the world of the "excluded middle", where something cannot be and not be at the same time. One of the great confusions of our time is trying to reconcile the habits of binary thinking with scientific knowledge and practice which increasingly challenges it. It's not just quantum physics where we are getting used to the idea of things being and not-being at the same time; politics is not longer left or right (if it ever was!); gender and sexuality is increasingly seen as non-binary; information analysis articulates contingency and mathematics itself embraces forms of expression such as category theory which embraces multiplicity in place of binary division. An important element in this is our approach to counting. What would our idea of economy look like if we counted differently? We've made our world fit our logic. Maybe it's time we made our logic fit our world.

In the world of education, we have conversations. The most important thing about an educational conversation is that it is sustainable, that it grows, and that through its continued development, the capacity for creative utterances increases amongst the participants. Our conception of knowledge and concepts themselves are embedded in this fundamental idea of conversation. And attempts to theorise conversation and discourse have become the cornerstone of theoretical development in educational technology. However, these theoretical developments (Gordon Pask and Niklas Luhmann are the most dominant theorists, Siemens and Downes's connectivism (I originally said 'constructionism' by mistake - but it is, isn't it?!) is a sub-domain of these basic ideas) embraced a logical ideal which was binary. Essentially concepts were treated as objects articulated by utterances, and these objects could be compared with one another (your concept of an elephant vs mine - are they the same, yes or no?).

For Pask, concepts themselves are a manifestation of stabilities in the discourse - concepts emerged through the dynamics of communication. It's all very computational. The problem with this view is that emotions got left out of the picture. But any teacher knows the importance of emotion in teaching and learning. The problem is that we don't have a way of embracing it in our logical ideas of education.

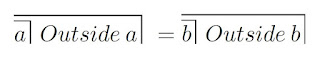

We have to step back from all of this to get to a different kind of logic of education. The first step is one of humility: that whatever we think education, or an educational conversation might be, there is a domain which is outside it. Any theory, and any logic draws a boundary around education. The trick is to stay focused on the boundary, not the thing inside it.

Any boundary invokes distinctions within it. Conversations involve words - concepts, utterances, and so on. Any concept also has a boundary. Any boundary has a boundary too. What emerges are recursive nested structures which might be expressed as a string:

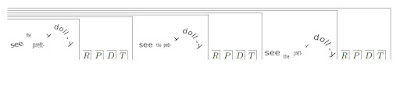

Perhaps one way of characterising this is to imagine a process of gradually rewriting the strings P and Q so that they become more similar. The rules for rewriting the strings arise from the relationship between the two strings, which might be thought of as the emotional relationship between two people. So, for example, if P is (((((A)B)C)D)E) and P sees Q initially to be ((W)V), then P might be rewritten (((((V)A)B)E). Lets say Q sees P initially as ((A)B). If Q then sees P as ((V)E), V is understood as something which a recognised common constraint between them. P might say to Q, "it's cold here, isn't it!"

P has learnt one of Q's constraints. P's rewriting continues like this to illuminate the structure of constraint in Q. As the structure of constraint is discovered by P, so P can reveal their own constraints (their conceptual knowledge) in a structure consistent with Q's constraints.

The principal technique of teaching - and the principal objective of the string rewriting process - is to produce multiple descriptions of constraints. In this way, a string, ((V)E) can become ((((V)Z)Y)E or further, ((((((V)Z)A)B)Y)E... and so on. Each description can be broken down into multiple distinctions, and those distinctions related to other distinctions. The clues for the rewriting come from the distinctions made about the structure of Q's constraints.

This is rather sketchy, but the point is that it is not a matter of "does the student know concept A or B?" (binary), but rather, "concepts A and B are part of the constraints of the teacher; these concepts are learnt when the teacher discovers the structure of constraint in the learner and articulates multiple descriptions of A and B which reveal the teacher's constraints in a way that the learner can understand". Distinctions are always transcended, with the production of further descriptions. In the end, there is only the continual production of descriptions.

I think this logic demands a radically different approach to educational technology. This gives me hope that we might be able to do something really powerful with our technologies in education, rather than simply presenting content or exchanging text messages.

In the world of education, we have conversations. The most important thing about an educational conversation is that it is sustainable, that it grows, and that through its continued development, the capacity for creative utterances increases amongst the participants. Our conception of knowledge and concepts themselves are embedded in this fundamental idea of conversation. And attempts to theorise conversation and discourse have become the cornerstone of theoretical development in educational technology. However, these theoretical developments (Gordon Pask and Niklas Luhmann are the most dominant theorists, Siemens and Downes's connectivism (I originally said 'constructionism' by mistake - but it is, isn't it?!) is a sub-domain of these basic ideas) embraced a logical ideal which was binary. Essentially concepts were treated as objects articulated by utterances, and these objects could be compared with one another (your concept of an elephant vs mine - are they the same, yes or no?).

For Pask, concepts themselves are a manifestation of stabilities in the discourse - concepts emerged through the dynamics of communication. It's all very computational. The problem with this view is that emotions got left out of the picture. But any teacher knows the importance of emotion in teaching and learning. The problem is that we don't have a way of embracing it in our logical ideas of education.

We have to step back from all of this to get to a different kind of logic of education. The first step is one of humility: that whatever we think education, or an educational conversation might be, there is a domain which is outside it. Any theory, and any logic draws a boundary around education. The trick is to stay focused on the boundary, not the thing inside it.

Any boundary invokes distinctions within it. Conversations involve words - concepts, utterances, and so on. Any concept also has a boundary. Any boundary has a boundary too. What emerges are recursive nested structures which might be expressed as a string:

String P: (((((A)B)C)D)E)Different people have different boundaries. Emotion is an indicator of a boundary. Teaching is a process of discovering and manipulating boundaries - in other words, changing the way people feel about things. A learner who is at first unknown, carries with them a set of concepts and boundaries about the world. They might be:

String Q: ((((W)X)Y)Z)VSome of these boundaries will be deeply felt. But we can start to become more abstract. Let's talk about these two strings. What does P know about Q? How might "coming to know" be characterised as transformations in the relationship between P and Q?

Perhaps one way of characterising this is to imagine a process of gradually rewriting the strings P and Q so that they become more similar. The rules for rewriting the strings arise from the relationship between the two strings, which might be thought of as the emotional relationship between two people. So, for example, if P is (((((A)B)C)D)E) and P sees Q initially to be ((W)V), then P might be rewritten (((((V)A)B)E). Lets say Q sees P initially as ((A)B). If Q then sees P as ((V)E), V is understood as something which a recognised common constraint between them. P might say to Q, "it's cold here, isn't it!"

P has learnt one of Q's constraints. P's rewriting continues like this to illuminate the structure of constraint in Q. As the structure of constraint is discovered by P, so P can reveal their own constraints (their conceptual knowledge) in a structure consistent with Q's constraints.

The principal technique of teaching - and the principal objective of the string rewriting process - is to produce multiple descriptions of constraints. In this way, a string, ((V)E) can become ((((V)Z)Y)E or further, ((((((V)Z)A)B)Y)E... and so on. Each description can be broken down into multiple distinctions, and those distinctions related to other distinctions. The clues for the rewriting come from the distinctions made about the structure of Q's constraints.

This is rather sketchy, but the point is that it is not a matter of "does the student know concept A or B?" (binary), but rather, "concepts A and B are part of the constraints of the teacher; these concepts are learnt when the teacher discovers the structure of constraint in the learner and articulates multiple descriptions of A and B which reveal the teacher's constraints in a way that the learner can understand". Distinctions are always transcended, with the production of further descriptions. In the end, there is only the continual production of descriptions.

I think this logic demands a radically different approach to educational technology. This gives me hope that we might be able to do something really powerful with our technologies in education, rather than simply presenting content or exchanging text messages.