Abstract

For many years now there have been well-funded project opportunities for developing educational innovations, both pedagogical and technological, to fulfil the educational ambitions of national governments and European agencies. These projects have been awarded on the basis of competitive bidding against themes identified by funders. Typically funding calls exhibit bold rhetoric as to their ambition and consequently bold claims are made in response. It is not untypical for the results of these projects to fall short of the rhetoric.

I argue that during the process of project delivery, there arises an unintended functionalism where the fulfilment of the project contract through the regulatory instruments of project funders overrides critical engagement with challenging objectives, rhetorical claims and critique of theoretical fundamentals. Two contrasting projects are examined to explore this phenomenon: ITEC, a large-scale technological innovation and implementation project involving schools throughout Europe; and INCLUD-ED, a research project to describe successful educational practice around inclusion. An analysis is presented which draws on Searle’s concept of ‘status functions’ to explain anomalies between the declarations about the function of the objects and concepts of a project (tools, concepts, divisions of labour), and evidence of project outcomes. I argue that project functionalism arises because the regulatory apparatus of the project is often the only common constraint bearing on all project stakeholders, and more broadly that shared constraints between stakeholder groups provides the conditions within which status function declarations can be upheld. The contrast between ITEC and INCLUD-ED presents an opportunity to ask whether and how, in the light of this knowledge, the pathology of project functionalism might be avoided.

Introduction: Projects and Status

Any theory, technology or pedagogic design is a declaration of the kind “this x counts as a theory/learning design/technology within context c”, where x is an assemblage of concepts, propositions or artefacts, and c is the community for whom the declaration is intended. However, just because declarations are made doesn’t mean that the validity of the claim will be upheld within the community. Within the field of educational innovations, both technological and pedagogical, declarations which ultimately are not upheld by the community they were intended for are commonplace. Laurillard has commented on this recently in discussing the claims of learning technologists and theorists:

“The promise of learning technologies is that they appear to provide what the theorists are calling for. Because they are interactive, communicative, user-controlled technologies, they fit well with the requirement for social-constructivist, active learning. They have had little critique from educational design theorists. On the other hand, the empirical work on what is actually happening in education now that technology is widespread has shown that the reality falls far short of the promise." (Laurillard 2012, p83)

Falling “short of the promise” is another way articulating a mismatch between claims by innovators and the experiences and expectations of end-users. Interestingly, here Laurillard doesn’t consider the possibility that the declarations inherent in theories upon which technical and pedagogical designs are founded might also be wrong: she goes on to restate her interpretation of Gordon Pask’s theory of conversational learning, first presented by her in 1999 (Laurillard, 1999), and instead points the finger at the institutional conditions of implementation for failure. Consequently, gaps between theory and practice persist as emphasis shifts away from theoretical description towards practical prescription. This has knock-on effects on project funders whose task is to design new funding calls based on existent theories and the state of current practice. As project follows project, whilst technologies fail readily, theories are rarely revised or rejected.

In this paper, I present Searle’s theory of social ontology as a means for thinking why this happens. I focus particularly on the vehicle for educational innovation, the funded educational project. Projects are the principal means for establishing new declarations about new technologies, pedagogies or learning designs. To understand the root causes for the disappointment that Laurillard articulates, we have to understand what happens in the educational project to the claims that are made about their impact. I present a study of two contrasting projects:

- ITEC – a large-scale technological innovation project involving schools throughout Europe for which a technological infrastructure was created and, ultimately, largely ignored.

- INCLUD-ED – a research project aimed at describing and amplifying “Successful Educational Actions” to enhance inclusion in education through the use of a “communicative methodology”. INCLUD-ED is one of a few EU projects recognised as “successful” (Net4Society, n.d.)

Using Searle’s theory, the declarations about theories, practices, technologies can be studied in the context of the different stakeholder groups within which they are made. The analysis suggests that coordinated action between different stakeholder groups occurs when there are identifiable shared constraints between different groups. The projects differ in the ways different groups share constraints, but in the case of both projects, the fundamental domain of shared constraint is the demand to acquiesce with the regulatory instruments of the project funder. To different degrees in each case, this gives rise to unintended functionalism which at best acts as a barrier to theoretical critique, and at worst encourages defence of indefensible propositions.

Searle’s ‘Status functions’ and Social Ontology

Searle introduces his concept of ‘status function’ as a way of accounting for those aspects of social reality which exist through human action, which he terms ‘ontological subjectivity’ (2010). Beyond material facts of physics (Searle calls this ‘ontological objectivity’), private sensations like itches (‘epistemic subjectivity’), or social facts like dates of battles, births or deaths (‘epistemic objectivity’), Searle argues that most of the social world is constituted by declarations of ‘status function’ as a particular kind of speech act made within a community who uphold it through their ‘collective intentionality’. Declarations are made by a social entity (a King, Government or a corporation) with sufficient authority (what Searle calls ‘deontic power’) to make an utterance of the form “X counts as Y in C” (e.g. “This paper counts as money in country c”). In arguing that the entities of the social world, (institutions, technologies, monarchies, etc) are all manifested as status function declarations held together through the ‘collective intentionality’ of communities, Searle goes beyond his earlier work on speech acts (1969), acknowledging a social reality which he previously appeared to ignore. In education, real things like textbooks, teachers, universities, degrees, timetables, curricula, league tables and learning technologies also can be seen to be status function declarations, and understanding this invites the study of how declarations are made, and under what conditions they are upheld.

Searle's idea has far-reaching consequences, enabling him to consider not only the reality of objects and institutions, but human rights, armed forces, nation states, gender identity and so on. I will not explore these further reaches here. However, status functions declarations are made about technology. The power to make such declarations rests variously with technical designers, pedagogical designers, project teams, occasionally teachers, and often managers. Many status function declarations about technologies or pedagogies – particularly from projects – fail to establish themselves in the communities for which they are intended. Consequently, the technology dies. Occasionally, a status function declaration is made such that the deontic power behind it is sufficient for the gradual emergence of broad social agreement that the status function is indeed valid (which is the case now for mobile phones, email and social software).

Any new status function is made in the context of many other established status functions within a society, institution or other social group. Typically technologies aim to disrupt established rituals of practice involving other kinds of object, practice and institutional structure. Additionally, every status function, as well as being a statement about what is what in context C, is also a statement about what is not what: in other words, a status function makes a distinction between what counts as x, and what doesn't. Status functions are both positive in affirming an object, and negative in declaring a constraint.

Given that status functions declare constraints, it would not be surprising to see different status functions competing with each other, or contradicting each other: each being the others' constraints. The status functions "I am the master" and "You are a slave" presents a simple example of where one status function is constrained by the other: the master requires the slave to acquiesce; the slave is constrained by the master in a way which is not advantageous, yet feels compelled to reinforce the master's power; fear leaves the slave unable to consider life away from the master's demands. The situation is called by Bateson a “double bind”. Within the master-slave relationship are the basic contents of social institutions, with rights, obligations, duties forming the mutually-constraining patterns of double-binds which characterise life in families, schools, universities, churches or corporations – indeed, mutual constraint appears a pre-requisite for the existence of any kind of institution.

Technological status functions produce similar patterns of mutual constraint through implicit rights, duties and obligations inherent in their usage. The assertion, usually by technology corporations, of the status of objects demands the acquiescence of users, whose emerging ritualised patterns of practice entail fears in breaking rituals which further entail the use of the tools about which the status functions are made. The daily reality of technologies is held in place by “knots” in the status functions which relate declarations of technological function with existing webs of social interaction and existing status functions. In social life, the status functions that each of us lives with comprise highly complex webs of mutual constraint: the intervention of a status function in a pre-existing web of status functions is particularly challenging. It is the inability to counteract the forces prevalent in existing status functions that most technologies fail. To say there is "nothing in it for me to use technology x" is to say that existing commitments demand the maintenance of practices which would be unnecessarily disrupted by a new technology. However, in order to understand how it is that some status functions actually do succeed in transforming the knots that people live within, it is important to understand the forces that keep the knots tied together. Since every status function is also a declaration of constraint, and that successful knots are patterns of mutual constraint, the role of shared constraints among the different stakeholders who are implicated in upholding the status of a state of affairs provides a way of exploring the dynamics that distinguish instances of adoption with non-adoption.

Case Study 1: The ITEC Project

The ITEC project set out to establish an ambitious technological infrastructure which would support both the execution and coordination of innovative pedagogy. Aiming to bring technological and pedagogical innovations closer to-hand for teachers across Europe, ITEC has sought to transform the context of teaching and learning in the hope that the agency of teachers would follow. Inspired both by the discourse on Learning Design (Koper, 2004; Laurillard, 2012) and by thinking about new opportunities for personalisation of learning through initiatives like the Personal Learning Environment (Johnson and Liber, 2008), ITEC’s vision encompassed greater personalisation and technological control by learners, coordinated with an infrastructure which would facilitate large-scale piloting and evaluation of educational ‘scenarios’. Whilst it has raised awareness of technology across Europe, allowing many teachers to experiment with different kinds of pedagogy (particularly inquiry-based, classroom flipping, etc), measured against its ambition to create a sustainable technological infrastructure to support 'the classroom of the future', ITEC (like so many other projects before it) has largely failed.

The focus here is on comparing the ITEC vision of “transformed teaching and learning” with its reality, investigating and explaining the difference between hypothesised social transformation and actual events. It is argued that phenomena which emerge in projects like ITEC are of significance for any attempt to intervene with new pedagogical schema, tools for encouraging pedagogical design, attempts to analytically determine learning needs, or attempts to reproduce formal education using technology. So often it seems the articulated visions of project teams appear as ‘naked emperors’ to those whom they wish to change. A study of ITEC reveals some clues as to why this might be.

Case Study 2: The INCLUD-ED Project

The ambitions of the INCLUD-ED project are, in a broad sense, very similar to ITEC. INCLUD-ED states:

“In today’s knowledge society, education can serve as a powerful resource to achieve the European goal of social cohesion. However, at present, most school systems are failing as shown by the fact that many European citizens, and their communities, are being excluded, both educational and social, from the benefits that should be available to all.”

INCLUD-ED involves a descriptive approach to studying educational interventions, with its focus on identifying what it calls “Successful Educational Actions” and “Integrative Successful Actions”. Its methodology seeks to identify those actions which evidence indicates similar beneficial results across different contexts. In identifying different outcomes in different contexts, INCLUDE-ED has been unified by a single methodological approach based on dialogue. Arguing that traditional research techniques tend to privilege one voice over others, the dialogic approach has been used to capture the voice of vulnerable groups including Roma, people with disabilities and so on. INCLUD-ED explains:

“While the voices of vulnerable groups have been traditionally excluded from research, the communicative methodology relies on the direct and active participation of the people whose reality is being studied throughout the whole research process. After years of doing research on them without them that has not had any positive repercussion on their community, the Roma refuses any kind of research that reproduces this pattern. With the communicative methodology, Romani associations have seen the possibility to participate in a research that takes their voices into account and provides political and social recommendations that contribute to overcome their social exclusion.” (INCLUD-ED, 2012)

The INCLUD-ED project is one of a number of EU projects which have been deemed by the EU commission to be successful. Aimed at establishing best practice for inclusive education, unlike ITEC, INCLUD-ED does not involve technological development per se, but rather involves the exploration of a number of different pedagogical scenarios. In the following analysis, the contrast between INCLUD-ED and ITEC can be seen in the relations between the different status function declarations within the project.

Status Function Declarations in ITEC and INCLUD-ED and their impact on Stakeholders

All projects involve a set of status declarations. The first and most important being the declaration, "This is project" which carries a set of rights, obligations and duties bearing upon the project stakeholders. The context within which this declaration has power includes the project management team, the funders, and the individuals with whom the project is conducted. Projects win funding by making assertions about the status functions they will bring into being. Typically, these are the “objects” of the project. For example, the ITEC project identifies through its project plan the following technologies and entities which it proposes to create:

- learning scenarios (a broad description of educational activity)

- a widget store (a repository of tools)

- widgets (a tool)

- learning activities

- a "composer" (a way of recording configurations of activities and tools)

- a 'people and events' database (a kind of educational CRM system)

- a learning shell (basically a container for educational activities, people and tools - e.g. a VLE)

- evaluation questionnaires

- a ‘shell’ for containing learning activities (basically, a VLE)

- national coordinators of ITEC activities in your country

Unlike ITEC, INCLUD-ED is not a development project, placing less emphasis on declaring new entities, but rather makes claims for the status of a “Successful Educational Actions” and “Successful Integrative Actions” by examining existing practices and their effects. INCLUD-ED makes assertions about a particular methodological approach, a “dialogical methodology”. Such claims are largely intended for an academic audience but which justify an approach which involves stakeholder engagement at a deep level.

Both projects are focused on what happens in classrooms. Teachers are the principal target for the above status declarations. However, teachers already inhabit a world of status declarations from various sources:

- "This is the headteacher of your school"

- "These are the professional expectations for your performance"

- "These are the children you are responsible for"

- "These are their parents"

- "These are the expectations the children's parents have for their children"

- "These are the league tables of your school (if they have them)"

- "These are the assessments the children will have to pass"

- "This is your timetable"

- "This is the curriculum"

Parents and students similarly will have a complex web of status functions to negotiate. It is not difficult to see that these two sets of status declarations may conflict with each other. Individual teachers, project officials, national coordinators, software developers, etc. have to make choices about their actions. Each status declaration presents an aspect of constraint against which choices must be negotiated: whilst each declaration makes a statement of the positive existence of a thing (headteachers, widgets, evaluation questionnaires) they simultaneously declare an absence - what isn't a headteacher, widget, evaluation questionnaire, and so on. A status function declaration is a distinction about a boundary.

For each individual, we might also consider “unarticulated” or “potential” status functions – what Harré refers to as an inner ‘storyline’ (Harré andLangehove, 2002): the things people might want to say, or declare in the future, but don't yet have the position or supporting evidence to articulate as their own status functions. Whilst these would not fall into Searle’s category of status functions (as they are not speech acts), they do form part of the “collective intentionality” within which actual status functions establish themselves. Within this space, we might consider personal ambitions, personal priorities in terms of caring for loved ones, maintaining a stable income, identifying domains for control and keeping one's job.

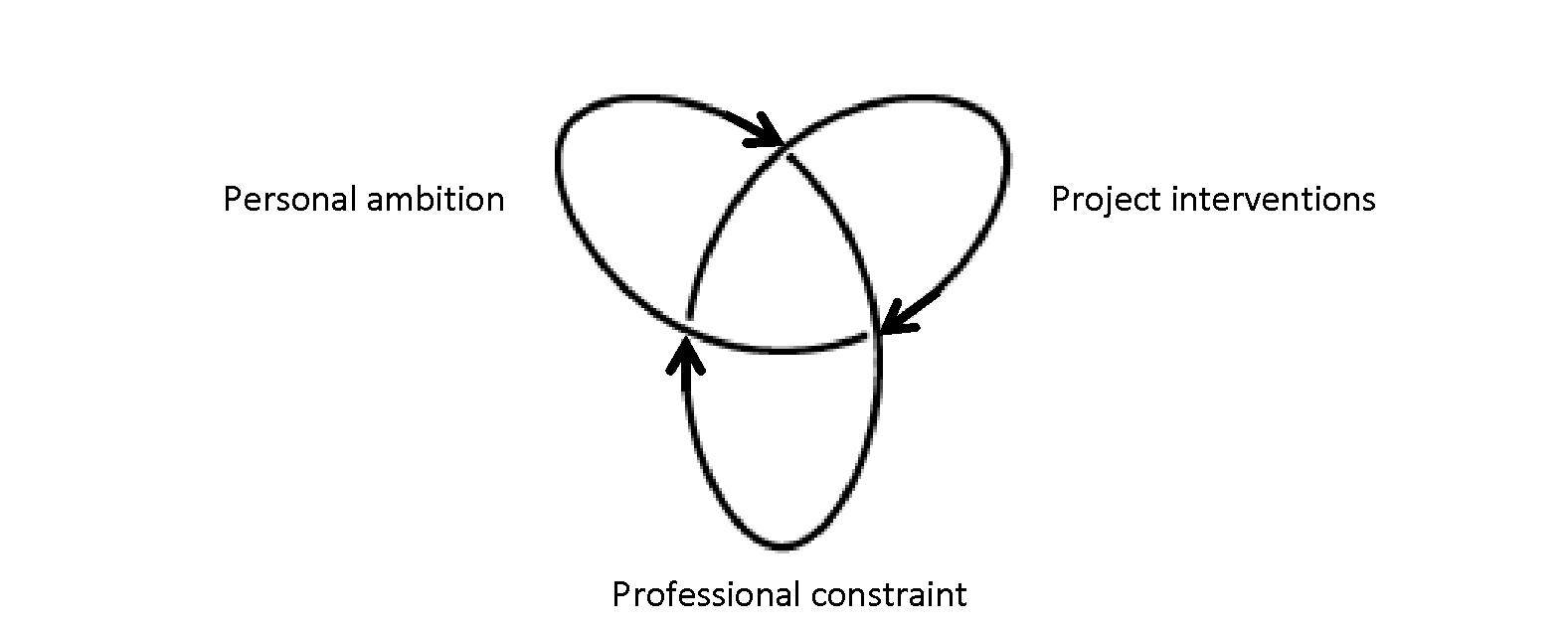

Any project has to negotiate its status declarations within the context of existing status declarations that already exist within the setting in which it wants to intervene. These in turn define the domain of collective intentionality for the project. Given that the potential for conflict between the expectations of different stakeholders, any project might hope that it establishes a dynamic between the inner wishes of individual stakeholders, the existing professional responsibilities of those stakeholders, and the innovations suggested by the project. In other words, it hopes that the intervention of the project creates a dynamic between constraints whereby the new innovations are established and held in place because of:

- The dynamic between individual ambition and professional constraint

- The dynamic between professional constraint and project interventions

- The dynamic between project interventions and individual ambition

Given these dynamics, we can visualise the knotted tensions inherent in the web of status functions and intentionality through the metaphor of a Trefoil knot (Kauffman, 1995). Each declaration is a constraint for the other, but each constraint holds the others in place:

The metaphor is useful because when trying to understand the intentions of a bidding team which makes status functions as part of their bid (as in ITEC’s status function), it will be hoped that new declared status functions produce social change precisely because they are successful in “tying new knots” in the lived experience of teachers and learners: so, for example, teacher x’s ambition shifts to seeing the adoption of technology z as crucial for their career advancement. Should this happen, then the technological adoption is achieved. Unfortunately, this rarely happens. In reality, the professional constraints of teachers with limited time and resources dominate and project interventions tend to get ignored and the education system tends not to change.

Evidence from ITEC: Stakeholder evaluation and action

The tensions between status function declarations are easily identified in the ITEC project. Both in its declared division of labour within the project team, and among the different artefacts and activities that each group is responsible for, the roles, responsibilities, duties and obligations of the project team are clearly defined. Most basically, there are those who are in charge of pedagogy and there are those who are doing software development and there are those who are trying to manage it all. Each group brings different constraints, and each group of stakeholders will be enmeshed in their own knots relating to their professional practice and personal wishes. Technology partners are responsible for upholding the status functions concerning project technologies (widget stores, composers, and shells) and pedagogical partners are responsible for developing learning scenarios, activities and engaging with school teachers in encouraging them to use technologies produced by the project.

For all members of the project team, there are other status functions, some of which some of which directly concern the management of the project, but others which relate to professional identities as academics of either education or technology:

- "This is the educational discourse"

- “This is the technology discourse”

- "These are the important journals to publish work"

- "These are the deliverables that must be achieved"

- "This is the budget"

- "These are the people who are involved"

- "These are colleagues with whom it would be good to make connection"

Project managers must make declarations which are meaningful to the project funders. The measuring instruments of any project are its deliverables, measurable success criteria, budgets and reports. Any change in project direction entails a new set of status function declarations which have to be agreed with the funders. Each aspect of the relation with funders can be seen to constitute status functions with inherent rights, duties and obligations between stakeholders. The critical issue concerns the relation of the status function declarations pertaining to the management of the project, and the status function declarations concerning the project’s activities – either in the creation of new technologies or innovative pedagogy.

ITEC widgets: the fate of a technological status function

As an example of how ITEC’s status function declarations related to the practice of teachers and the instruments of project funders, the creation of ITEC’s ‘widget store’ is instructive. The idea of the widget store was to create a repository of educational tools which could be easily dropped-in to existing school technologies by teachers. In ITEC, the developers asked the national coordinators (who oversaw the activities of teachers in their countries) “How does the widget store fit with the overall vision/philosophy of education in your country?” In response, stakeholder comments appear to attempt to balance a rejection of the technology whilst maintaining commitment to the project’s ideals. For example, one National Coordinator responded:

“The teachers involved in the iTec project are pretty well-skilled in the use of technology so the widget store is another source of tools among others they still have available. So to make the widget store more attractive we introduced it as tool to include their own content into the shell, and to share it with other iTEC teachers who are using shells as well.”

The statement is interesting because whilst effectively presenting the case that the Widget Store was surplus to requirements, upheld another technological status function of the project, the Shell. Shells are more broadly defined than widgets (practically anything can count as a shell!), and so the commitment to shells over widgets was a way of maintaining commitment to the broader status functions of the project whilst rejecting the specific widget technologies.

A more positive statement in response to the same question came from another country’s education ministry:

“In terms of the vision of education here, there is definitely a change in education relating the teachers training and expectations of them regarding using 21 century skills – especially using technology. There is a very big education program of adapting the educating system to the 21st century with emphasis on using technology – therefore in terms of vision and philosophy – the widget store definitely fits the education system”

In effect, this questionnaire response reproduces the project’s own rhetoric without any firm commitment to any of the technologies: again, a strategy for maintaining commitment to the project whilst avoiding specific technology commitments which would have interfered with daily practice.

Even when responses are a little more blunt, there remains some degree of equivocation and strategic negotiation of the status functions of the project:

“For 13-15 yr old age group it doesn’t really fit with the curriculum. It has been used across a number of subject areas.”

In the light of this comment, one would expect to see indications of usage from web statistics since the technology has been used across the curriculum. However, the web statistics remain low for access to the tools. This is a statement which claims compliance with the project processes, but rejects the project technologies: again, a way of maintaining a connection with the project without engaging in new practices which might disrupt the status quo. A similar problem of disparity between the low web statistics and positive reports emerges from another national coordinator who enthusiastically said: “[we] have continuously worked with the Widget Store - it is one of the highlights of the iTEC project.”

An indication of the kind of tensions existing when trying to establish the technology was expressed by a participant who said:

“We ask teachers to experiment with the Widget Store because it is a structural part of iTec. The main challenge […] is to ask teachers to experiment with a technology that they are not familiar compared with the ones they already use. […] most of the iTec teachers are advanced, so they prefer to use technology they already know (and trust), experimenting more in pedagogy.”

This is to affirm commitment to the pedagogical side of ITEC at the expense of the technological side. Some respondents were more positive about the technology, although tending to acknowledge the project rhetoric rather than committing to the new tools:

“Most teachers said they would like to continue to use the tools after the project, especially if there are more resources”

“When you become familiar with the Widget store, it offers access to a range of valuable/quality resources. It keeps students focussed on what they are doing”

The Widget Store was not the only status declaration of the project, but engagement with it demanded significant disruption to existing practice which most teachers were unwilling or unable to engage with. Rejection of the technology by participants was defended by a number of teachers, but this rejection was reported in a way which didn’t damage commitment to the project as a whole. All stakeholders appeared willing to commit to the project goals (the rhetoric) but in a way that would be least disruptive to their existing practice.

This raises questions about the reasons for maintaining commitment to the project, but not to the tools. The project without the tools was effectively a set of rhetorical claims of educational innovation, and loose status function declarations concerning “pedagogical scenarios”. For teachers, association with the project (the status of being an ‘ITEC teacher’) carried some weight within their individual schools and provided opportunities for engaging in a broader discourse outside their immediate environment. If these commitments could be maintained, together with engagement in the instruments of the project (evaluation processes, training sessions, etc) then the project could be integrated into the web of status functions that teachers were already immersed. However, this strategy puts the emphasis on the instruments of the project management, and not the specifics of its technological and pedagogical aims. In this way the management devices which were intended merely to steer the project towards realisation of a technological and pedagogical vision become the principal status functions which constrained all the stakeholders.

INCLUD-ED Status Function Declarations and Declared Social Impact

INCLUD-ED is unequivocal in the assertion of its achievements:

“knowledge transfer between research and institutions, practitioners and end-users has been effectively achieved. SEAs has been extended and implemented in diversity of national contexts accounting for the support of institutions and local administrations. In order to do so, the coordinator institution has signed several agreements with local administrations, trade unions and universities, to make the SEAs accessible to more people who benefits from the research results.” (INCLUD-ED, 2012, p74)

In terms of status function declarations, knowledge exchanges involve a status function in one domain being carried over into another: in Searle’s terms, it is the status function declaration of “X counts as Y in C1”, followed by “X counts as Y in C2”. In moving from C1 to C2, there may of course be change in the collective intentionality of the new context, C2, partly caused by the increased deontic power of successfully making the declaration in C1. However, much is obscured in the statement that knowledge exchange has been successful and whilst evidence is provided of press reports about various initiatives in European education stemming from INCLUD-ED, and through mentions in EU policy documents, the actual details of the differences and similarities between contexts and interventions, and the causal power of INCLUD-ED’s original distinctions are hard to establish.

Given that INCLUD-ED is an academic research project, the production of academic outputs is perhaps unsurprising. INCLUD-ED’s claim that:

“The project’s major findings have been published in relevant international and national journals. Among the 70 paper publications produced, 25 of those have been published in the journals ranked by the ISI JCR […] Additionally, INCLUD-ED’s finding have been presented, and well received, at the most important international scientific conferences the field of education sociology” (INCLUD-ED, 2012, p70)

is impressive although not surprising - particularly for a project fundamentally oriented to analysing existing practice from an innovative methodological angle. Each publication is a status function declaration, and the academic discourse provides a domain of ‘known collective intentionality’ where successful publication is relatively straightforward for professional academics. Furthermore, within a project team comprising academics, there will be collective intentionality about which journals to publish in, things to write about and so on. Whilst publications alone don’t indicate success on the ground, their presence helps to increase the deontic status of the project in supporting claims for its effectiveness. INCLUD-ED’s emphasis on a dialogic method suggests that it is not status function declarations that matter per se, but rather a process to identify the collective intentionality of groups within which certain practices dominate. INCLUD-ED sets out to identify the status function declarations of existing practices and the collective intentionality which supports them, rather than determines the status function declarations that it somehow has to create the conditions for adoption.

The manner of INCLUD-ED’s project organisation is also interesting in comparison to ITEC. INCLUD-ED features a number of “projects” ranging from literature reviews, to particular longitudinal case-studies. By dividing its work into different projects and having those projects working with different stakeholders, effectively INCLUD-ED could pass the ‘deontic power’ for making status function declarations to sub-teams who could then manage their own activities relatively autonomously.

The dialogical process of INCLUD-ED is overseen by a set of committees including an advisory committee comprising people from vulnerable social groups and a panel of experts including experts and scholars in the field. INCLUD-ED is a consensus driven project, where the principal status declaration that is made is the importance of community engagement and the representation of stakeholder voices. It keeps its status function declarations to a minimum by asserting its method and goals of identifying “Successful Actions”. INCLUD-ED claims impact on policy through citation of its work of its approaches in policy documents. This enables INCLUD-ED to make the status function declaration “This is our impact” – principally for the benefit of those funding the project.

Whilst INCLUD-ED’s dialogical approach appears far more sensible than ITEC’s long list of technologies-to-be-made, it should be noted that INCLUD-ED made no attempt to transform practice in the way that ITEC did. INCLUD-ED sought to identify and reproduce successful practices. If there is a problem with the dialogic method it is the fact that the approach privileges consensus between participating groups rather than individual differences. Moreover, the emphasis is on evidence for success in the form of educational performance metrics: there is little appetite for engaging in deeper critique of the different interpretations of success in education. In this light, the communicative methodology appears as a kind of pragmatic strategy for achieving success in the eyes of funders and stakeholders. However, this kind of pragmatism in ‘following the crowd’ has attracted criticism, most notably from Horkheimer, who saw it as part of the march of technocracy:

"the life of each individual, including his most hidden impulses, which formerly constituted his private domain, must now take the demands of rationalization and planning into account: the individual's self-preservation presupposes his adjustment to the requirements for the preservation of the system. He no longer has room to evade the system. And just as the process of rationalization is no longer the result of the anonymous forces of the market, but is decided in the consciousness of a planning minority, so the mass of subjects must deliberately adjust themselves: the subject must, so to speak, devote all his energies to being 'in and of the movement of things' in the terms of the pragmatistic definition" (Horkheimer, 1947)

Given that many of the recommendations of the INCLUD-ED project might well have been written without the support of the project, questions remain about the real purpose of INCLUD-ED’s methodology. These questions concern the broader goals of educational projects, and the relationship between the agendas of governments and project teams in directing projects.

The emergence of project-functionalism as the binding force of a project

Having considered the relations within the project team, we can turn to the collective intentionality that is shared between project team and the project funders and reviewers. These relationships are determined by a set of status function declarations which are contained in the project plan documentation in the form of deliverables, milestones, measurable success criteria, dissemination activities and so on. In most projects, the ambition of broad aims has to be reduced to a set of measurable indices by which funders can be assured of claims for the success and effective operation of the project. There are measurable targets for the number of interviews conducted, the number of case-studies explored, the number of users using a tool or the number of papers published. If deliverables are deemed inadequate or targets not met, then the project risks being stripped of its funding, with various unpleasant implications for all project stakeholders. The collective intentionality that binds funders with project management concern these primary shared constraints.

ITEC and INCLUD-ED provide contrasting examples of how this can affect project activities. Among ITEC’s status function declarations was the identification of different groups of stakeholders whose primary concerns were either pedagogical, or in developing technology. Each group took responsibility for separate but interconnected parts of the project, and each group had a set of measurable outcomes to fulfil their part of the project contract. These included the number of classrooms where innovations took place, number of users of the technology and the number of innovative learning scenarios created. The results of the project, captured in the interviews discussed above, demonstrate that the “collective intentionality” of ITEC teachers was held within a web of constraints of which the project objectives were one aspect. Most importantly, each stakeholder was either directly funded (key project personnel) or supported in their activities (teachers) and consequently bound in various ways to the contract of the project whereby support could be withdrawn in the absence of engagement or success. The equivocal responses of teachers and the mismatch with real evidence of engagement with tools in ITEC demonstrates the balance that they attempted to create between satisfying the instruments of the project management and compromising other commitments and status function declarations pertaining to their professional practice. Moreover, the dominant presence of the status functions of the project plan meant that changing project direction or methodology entailed an onerous renegotiation with funders. Inevitably, compromises meant that the underlying status function declarations were preserved and flexibility to evolve was restricted.

By contrast, INCLUD-ED’s dialogical method and its effort to describe and amplify existing practice rather than generate new practices, enabled it to make far fewer status declarations. At the same time, INCLUD-ED benefited from not having a remit to make direct interventions in designing learning to see if they worked (or to find out they didn’t). The dialogical method was really a way of identifying the collective intentionality of stakeholder groups. INCLUD-ED had targets to publish results in journals, influence policy, to address a certain number of case-studies and so on, and each of these it could fulfil. However, the lack of critique of the project methodology, or its definition of success suggests there were still some areas of intellectual engagement which were precluded because of the contractual relationship with funders.

Implications for Designing Learning: Plans and Intersubjectivity

The contrasts between ITEC and INCLUD-ED are instructive when we consider the challenges of designing learning. The status declarations of ITEC (to a great extent) and INCLUD-ED (to a lesser extent) can be seen as declarations of anticipated futures, or plans. More generally, designs for learning are explicitly plans. When considering any project which seeks to ‘design learning’ the status function declarations are expressions of future imagined scenarios:

- “This is a design for learning about the Versailles treaty”

- “This is a MOOC on quantum physics”

- “This is a tool for creating learning designs”

- “These are the learning analytics for the course z”

The issue of planning and the extent to which plans are upheld as valid or not throws the spotlight back onto the human relations of project funders and bidders and to the collective intentionality that supports one plan over another. Both ITEC and INCLUD-ED had their plans supported; projects that didn’t get funded did not have their plans supported.

Both Searle’s theory and INCLUD-ED’s dialogical method acknowledge some debt to Schutz’s theory of ‘intersubjectivity’ within which ‘planning’ occupies a particular area of concern. Schutz, whose work developed Husserl’s original idea of the ‘intersubjectivity’, argues that

“there is a great difference between action actually performed and action only imagined as performed. The really accomplished act is irrevocable and the consequences must be borne whether it has been successful or not. Imagination is always revocable and can be revised again and again. Therefore, in simply rehearsing several projects, I can ascribe to each a different probability of success, but I can never be disappointed by its failure. Like all other anticipations, the rehearsed future action also has gaps which only the performance of the act will fill in.” (Schutz, 1971, p77)

However, Schutz also makes a distinction in intersubjective relations between face-to-face relations and what he calls the “world of contemporaries” or the “pure ‘we’-relation”. Plans for classroom practice and pedagogical designs have always been implicitly articulated by teachers and institutions, upheld by institutional and societal declarations of the curriculum, timetables, and so on. Some aspects of planning for learning are conducted with the face-to-face relation in mind; others consider the “world of contemporaries”. As with all plans, there are gaps for the teacher to fill in the flow of practice. However, a declaration of a plan within a face-to-face context such as “This is a course on Java Programming” entail different adjustments to practice if the same declaration is made in the more general world of contemporaries (for example, in a MOOC on Java Programming). In Searle’s terms, the difference between the declaration within the face-to-face context and the broader world of contemporaries entails fundamental differences in the conditions for collective intentionality, and differences in the rights, duties and obligations within the community.

Schutz’s concept of intersubjectivity is significantly more refined than the intersubjectivity described in Flecha’s (2000) dialogical method upon which INCLUD-ED is based, and indeed Searle does not explore the differences in interpersonal relations and how this might affect collective intentionality. Schutz’s intersubjectivity is about far more than conversation, presenting a social model which addresses Horkheimer’s criticism of Dewey’s pragmatism. It concerns the spectrum of human relations from face-to-face intense engagements to engagements with people who we don’t know very well, to engagements with ancestors and imagined engagements with successors.

Projects have to make plans within the context of the “we-relations” of academic discourse and the criteria of funders, with little knowledge of the actual lives or thoughts of project funders, but seek interventions in face-to-face domains where they have little understanding at the outset. In both learning design and in project design, the transposition of status functions from face-to-face situations to “we-relations” and vice-versa can cause problems of interpretation among stakeholders, and in the world of we-relations, there is little scope to adjust interventions to make the communications work. A dialogical methodology such as INCLUD-ED’s at least presents an opportunity for establishing collective intentionality on a face-to-face basis before any status function declarations are made by the project. However, ITEC too had many face-to-face meetings. Yet as Schutz observes, on leaving the meeting, individuals return to their relations in the world of contemporaries. In ITEC, despite face-to-face meetings, it was often difficult to bridge the gap between the face-to-face relations and remote relations. In the end, these difficulties meant that the only common constraints that existed concerned the management instruments of the project and that ultimately this proved to be the focus within face-to-face meetings too.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Whilst very different, the two projects studied highlight the same problem from different angles. As a project, some of ITEC’s technological interventions appear to have been unnecessary. However, the simple failure of technological interventions produce important knowledge outcomes which are at least as, if not more, significant than successes. Whilst a common recommendation within modern development projects is to “fail fast”, the criteria for failure are rarely clear, and even hopeless technologies will have vocal and articulate champions to the very last. Theoretical clarity can produce the conditions for asking “are our results what we expect?” or “are our theories right?” In the absence of theoretical clarity, coordinating effective ongoing evaluation is challenging – particularly when issues of software design suggest that the current intervention simply needs “tweaking” in order for it to produce the expected results. I have argued that the making of status function declarations in the absence of collective intentionality to support it is a recipe for failure.

ITEC committed itself to a large set of status function declarations at its outset, with only weak mechanisms to re-orient itself once stakeholder engagements had commenced and the actual collective intentionality could be analysed and project initiatives rethought. More critically, the status function declarations formed the core of the project management contract with the funders which meant that to rethink interventions would have entailed quite a significant renegotiation of the project contract. BY contrast, INCLUD-ED appears as a ‘model project’. The differences are clear:

- INCLUD-ED didn’t make nearly as many status function declarations;

- As a research project, the status function declarations it did make needed only to be upheld within the academic community of the project with the acknowledgement of the funders, rather than be supported by a wider constituency;

- The communicative methodology was an instrument for identifying collective intentionality meaning that any new status function declarations could harmonise with existing expectations (for example the declaration of successful educational actions);

- INCLUD-ED’s project organisation in separating itself into separate projects, was effectively a way of passing on the deontic power for making status declarations at a local level, rather than from senior management;

- INCLUD-ED’s acquiescence with regulatory instruments was fairly straightforward and did not appear to produce the kind of contradictions that were found in ITEC.

Having said this, INCLUD-ED, unlike ITEC, did not have to create interventions which were at risk of failure. INCLUD-ED had little scope to reflect on different interpretations of success or alternative futures which may or may not be viable. At the same time, Horkheimer’s worry about a crowd-driven approach remains a legitimate and relevant concern in INCLUD-ED, partly indicated by the absence of a critical voice concerning the project’s methodology.

The essential advantage of INCLUD-ED’s “communicative methodology” is pragmatic: essentially it meant that all other status function declarations can be pushed down into low-level layers of project beyond the concern of funders. Yet whilst the underpinning theory of the communicative methodology cites other work including that of Mead, Schutz and Vygotsky, the subtleties of the often quite considerable differences between these thinkers’ works is not explored. INCLUD-ED’s conception ‘intersubjectivity’, is unlikely to withstand the critical attention of scholars of those whose ideas are cited as foundational (particularly Schutz). Without taking anything away from the practices identified in INCLUD-ED, real differences in intersubjective experience are inevitably flattened by the need to establish consensus within stakeholder groups, and this in turn reflects the coordinating mechanisms of the project management and its relationship to funders.

In conclusion, there is first a question as to whether and how unintended functionalism in projects might be avoided, but there is also a question concerning why there is so little theoretical critique, development or refinement in projects. These two issues are related. At a practical level in response to the first question, a project with the aims of ITEC did not need to commit to making such a bewildering array of technologies. ITEC could have embraced a more dialogical method, identifying the collective intentionality of teachers and encouraging new technological practices in harmony with existing concerns. At the same time, there is a balance to be struck between exploring new possibilities which may not work and understanding the constraints within which individual stakeholders operate. To achieve this, reflexive processes of theoretical development, critique and refinement are required which both generate new possibilities for technologies and practice and adjust existing theories in the light of experience. Theories however are themselves status functions made by academics with an academic community which shows little inclination for upsetting established theory (or established academic egos) - even in the face of evidence that a theory's explanatory power is limited. Yet, the combination of reflexive and agile theory-building with effective practical intervention and measurable outcomes represents a way forward for scientific engagements in educational innovation: one which both maximises participation and inclusion in educational design, whilst mitigating the pathological effects of project regulation.

References

Bateson, G (1972) Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, evolution and Epistemology University of Chicago Press

Flecha, R (2000) Sharing words: Theory and Practice of Dialogic Learning Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Horkheimer, M (1947) The Eclipe of Reason Oxford University Press

Searle, J (2010) Making the Social World: The Structure of Human Civilization OUP

Searle, J (1969) Speech Acts: An essay in the philosophy of language Cambridge University Press

Schutz, A (1971) Problem of Rationality in the Social World, in Brodersen, A (Ed) Collected Papers, Vol II Studies in Social Theory Martinus Nijhoff: The Hague

INCLUD-ED (2012) Strategies for inclusion and social cohesion in Europe from education D. 25.2 FINAL INCLUD-ED REPORT available online at http://www.nesetweb.eu/content-resource-library/strategies-inclusion-and-social-cohesion-europe-education-includ-ed-final (viewed 25/7/2015)

Johnson, M; Liber, O (2008) The Personal Learning Environment and the Human Condition, Interactive Learning Environments, Vol 16, no.1

Kauffman, L.H. (1995) Knots and Applications Singapore: World Scientific

Koper, R (2004) Educational Modelling Language: Modelling reusable, interoperable, rich and personalised units of learning, British Journal of Educational Technology, vol 35, no. 5

Laurillard, D (2012) Teaching as a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology Taylor and Francis

Laurillard, D (1999) Rethinking University Teaching: A Conversational Framework for the Effective Use of Learning Technologies Routledge

Luhmann, N (1995) Social Systems Stanford University Press

Net4Society (n.d.) Success Stories: Impact of Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities, available online at http://www.net4society.eu/public/382.php (viewed 25/7/2015)