Gregory Bateson's famous but somewhat mystical phrase raises as many questions as it attempts to address. In essence it is an appeal for holism - particularly the kind of holism that cybernetics specialises in: the reduction of the world to the interactions of recursive processes. In this sense, 'pattern' is an allusion to 'abstraction' - the description of a mechanism. Bateson himself created many abstractions: 'double description', 'double bind', 'levels of learning', 'schizmogenesis', etc. In his language, these things are seen to be patterns by virtue of the fact that they repeat themselves at different levels of recursion, and much of his work was focused on unpicking the presence of these patterns in biological, sociological, anthropological and mathematical/logical domains.

Holism, as understood by cybernetics, is precisely this identification of recursive repetition, or 'patterning'. The cybernetic abstraction is the 'explanatory principle' (another Bateson term) which is applicable at many levels: a "defensible metaphor", as Pask would say.

But I'm wondering if this is a particular understanding of holism. The question is "does this understanding of holism leave anything out?" I'm worried that it might.

My worry is grounded in a suspicion that the holistic explanatory aspiration of cybernetics cannot account for the personal desire to hold to a holistic explanatory principle. Erich Fromm wrote about this is "Haben und Sein". He points out that there is much in theological discourse that guards against the kind of Faustian ambition of being able to explain everything - to "have" an explanation. It's probably better to "be" an explanation (although that's hard to explain!) - it's the kind of thing that Jesus or Buddha attempted to get across.

It all comes back to our relationship with abstraction. I've struggled with this, and if I attempt to 'explain' abstraction, then I'm thinking of saying:

Abstractions have to be learnt by others. Indeed, if they are not taught and learnt, there is no point to them. So I'm also thinking of saying:

It's very much like the relationship between music as played and music as notated. A performance is the process of creating redundancy from the abstraction of the score. Notation - which is the hard job of all composers - is the process of distilling experience into notated redundancies. [this is helping me think about my own difficulties in composition]

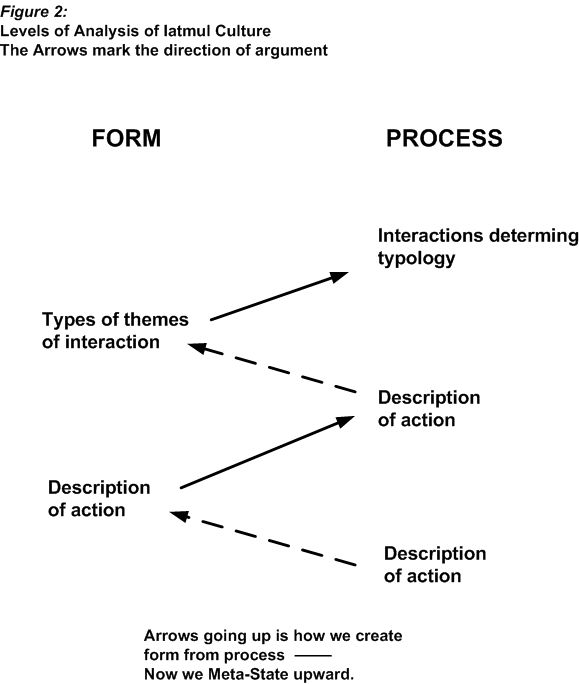

Bateson does talk about the relationship between classification and process (in "Mind and Nature" - where he reproduces this diagram from his anthropological work)

Holism, as understood by cybernetics, is precisely this identification of recursive repetition, or 'patterning'. The cybernetic abstraction is the 'explanatory principle' (another Bateson term) which is applicable at many levels: a "defensible metaphor", as Pask would say.

But I'm wondering if this is a particular understanding of holism. The question is "does this understanding of holism leave anything out?" I'm worried that it might.

My worry is grounded in a suspicion that the holistic explanatory aspiration of cybernetics cannot account for the personal desire to hold to a holistic explanatory principle. Erich Fromm wrote about this is "Haben und Sein". He points out that there is much in theological discourse that guards against the kind of Faustian ambition of being able to explain everything - to "have" an explanation. It's probably better to "be" an explanation (although that's hard to explain!) - it's the kind of thing that Jesus or Buddha attempted to get across.

It all comes back to our relationship with abstraction. I've struggled with this, and if I attempt to 'explain' abstraction, then I'm thinking of saying:

"abstraction is the removal of redundancy from the flow of experience"But abstraction creates its own flow of experience. So no abstraction can be complete. We're into a territory that requires a kind of Cantor-like diagonal argument...

Abstractions have to be learnt by others. Indeed, if they are not taught and learnt, there is no point to them. So I'm also thinking of saying:

"learning an abstraction is a process of recreating the redundancy that was removed in the abstracting process"and what about teaching?

"teaching is the process of creating the conditions for the production of redundancies related to a particular abstraction"but this is all getting a bit abstract!

It's very much like the relationship between music as played and music as notated. A performance is the process of creating redundancy from the abstraction of the score. Notation - which is the hard job of all composers - is the process of distilling experience into notated redundancies. [this is helping me think about my own difficulties in composition]

Bateson does talk about the relationship between classification and process (in "Mind and Nature" - where he reproduces this diagram from his anthropological work)

But the essence of the problem with abstaction (essence is another abstraction!) is that we lose sight of our own personhood, and the particular importance of "love" in being a person. As Faust realised, it is impossible to get beyond love, and whilst it is tempting to abstract it away (to remove its redundancy), to do this is to remove our humanity. If I say that "love is only redundancy" it reminds me of the damage that abstractions can do (although "loving" is partly "abstracting"...)

We cannot know the pattern which connects. But we can know the source of our desires to abstract knowledge. Knowing this, we might know ourselves and each other better. Then we might be in a position not to abstract further, but to do the opposite. To love the world more and to create redundancy.