Heterophony is a musical technique where the flow of a single melodic line is followed by many voices, where each voice has a slightly different variation. It is, like repetition and harmony, one of the fundamental forms of redundancy in music. It is also perhaps the most interesting because it reflects the ways in which a single structure unfolding over time can be represented in multiple ways. These multiple ways come together because the heterophony arises from the fact that we are all fundamentally the same, with a bit of variation.

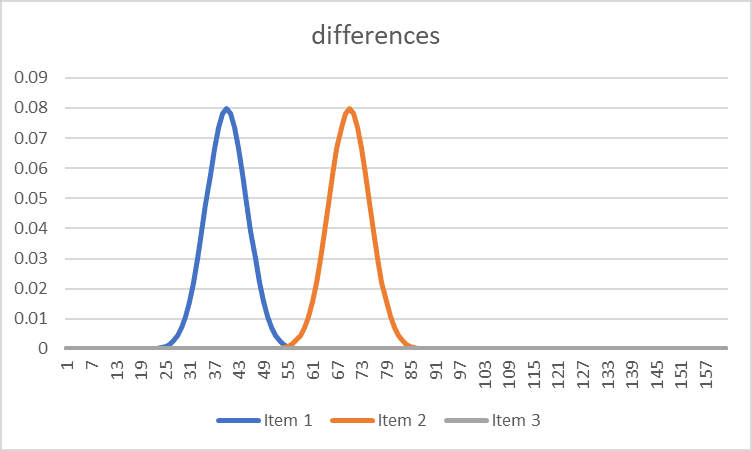

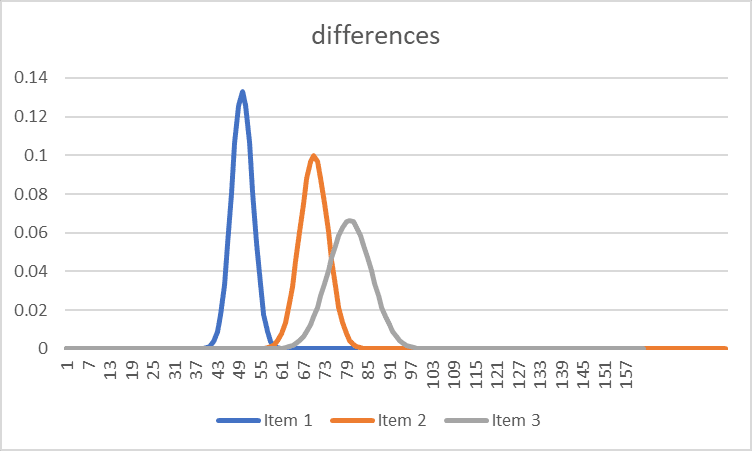

There is a certain sense in which AI is heterophonic. It obviously relies on redundancy in order to make its judgements, and with things like chatGPT, the redundancy is increasingly obvious not just in the AI itself, but in human-machine relations. All AI relies on the differences between heterophonic voices in order to learn. We seem to be similar in our own learning.

From a musical point of view, heterophony is most closely associated with non-Western music. Among the western composers who developed it in their music, the most striking example is Britten. While some of Britten's heterophony is a kind of cultural appropriation, I've been wondering recently whether he discovered something in heterophony which was always in his music. The predominance of 7ths and contrary motion in his very early "Holiday Diary" suggests to me a kind of heterophony which, by the time of his last (3rd) quartet (https://youtu.be/AElJ08gIOOM - particularly the first and last movements) becomes distilled into a very simple and ethereal world of crystalline textures. The fact that he went via his discovery of Balinese music was not an indication of appropriation, but self discovery. Unlike Tippett, he didn't say much about his thought and processes, but like all great artists, he might have been picking something up from the future - or rather, something that connects the future with the past.

There is something of this heterophonic aspect to early music (lots of it in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, for example). While parts move not so much in unison but in 3rds and 6ths, the rhythmic interplay of one part moving slowly and other parts moving much more quickly is very similar to the rhythms that unfold naturally through the interactions of heterophony. I'd always taken this rhythmic polyphony as a sign of unity in diversity, but the connection to heterophony gives it more depth for me - particularly now.

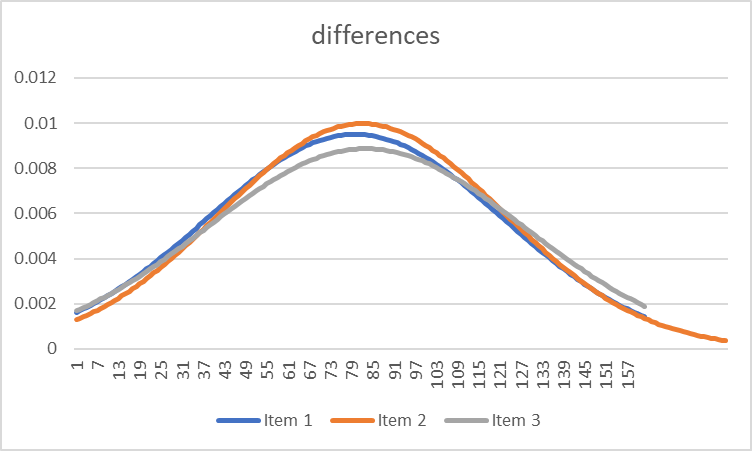

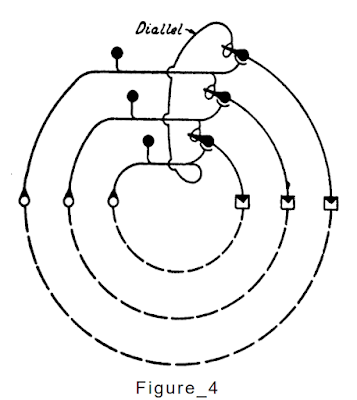

So what about heterophony today? We have got used to a particular kind of redundancy in music produced through harmony and tonality. It is partly the product of the enlightenment, and it places the order of humanity above the order of nature. AI is generating a human-like order of utterances by decomposing a kind of natural order, and its decomposition process is both fundamentally heterophonic and fractal. AI works like a singer in a heterophonic choir, listening to where the tune is going, calculating which way it will go next, and checking to see if it was right or not. In this process, there is difference, form, fluctuation of constraint, expectation, and relation.

We have an urgent need to understand this process, and heterophonic music provides us with one way of doing it. Also, perhaps curiously, it takes us away from the enlightenment mindset which on the one hand has given us so much, but which has also done so much damage to our environment. It is not Victorian orientalism to connect with fundamental processes that steer our collective will and judgement-making. But there may have been more to the pull of orientalism than mere fashion. I suspect Britten saw this.

Maybe Britten wasn't tuning-in to the way AI works (how could he?), but rather he was tuning in to something that is intrinsic to our biology. Is our physiology heterophonic? Is quantum mechanics? The fact that our AI is is perhaps also a reflection that there is something in us which has always been this way. This, to me, is another reason for us to listen more carefully. Not that we should listen to the same thing, but look out for the stream and try to follow it.

While there are tremendous technical advances being made at breakneck speed at the moment, understanding where we are culturally and spiritually is vital. We have existed for many decades in a fog where our ability to reconcile our physiology with our technology has led to a tragic disequilibrium. We have almost ceased to believe that a new equilibrium is possible. But it might be.