One of the most unfortunate aspects of increasing interest in topics like complexity and systems is the appropriation of scientific terminology to obfuscate the kinds of problems which the systems sciences were developed to enlighten. It's not exactly the same problem as Sokal (Fashionable Nonsense - Wikipedia) identified 20 years ago as a kind of intellectual scientific posturing - that, he argued, was at worst a kind of fraud, and at best, intellectual laziness. What we see now is more of the latter, but it exists in a dominant normativity where it's almost impossible to suggest that simply saying stuff is "complex" is to do no more than posit a blanket "explanatory principle" which explains away intellectual difficulties, rather than invites the question "how? so then what?".

Entanglement - as it has been used by Latour and others - is a case in point. Latour has positioned himself carefully here (see Bruno Latour, the Post-Truth Philosopher, Mounts a Defense of Science - The New York Times (nytimes.com) because he is aware of the problem (and as someone who began their career doing information theoretical analyses, he should know), but that hasn't stopped a sociomaterial industry (particularly in management science and education) growing up with long words and nothing much to say. Like all industries, it seeks to defend its position, which makes challenging it very difficult, and any practical educational progress even less likely.

In physics, entanglement refers to the specific state of affairs in quantum mechanics where non-local phenomena are causally connected in ways which cannot be explained by conventional (Newtonian, locality-based) physics. If there is a fundamental underpinning idea here, it is not so much the weird interconnections between what might be seen to be "separate" variables, but rather the distinction between local and non-local phenomena, and the ways in which the totality of the universe is conceived in relation to specific locally observable events. Talking about entanglement without at least considering it in the light of totality and non-locality is like talking about the reality of ghosts on a fairground ghost train.

Part of the problem is that we have no educational cosmology - no understanding of totality, or rather how education fits in a totality of the universe. This seems a grand and ambitious task - but if we deny that such a thing is possible, we then cannot defend allusions to science to help us address educational problems. This is why better educational thinkers are thinking about physics, education, technology and society together (this is good: Against democracy: for dialogue - Rupert Wegerif). James Bridle's new book "Ways of Being" is also better - containing a lot of good stuff about biology and cybernetics - although again, it's hard to see a coherent cosmology... (very interesting interview between him and Brian Eno here: Brian Eno and James Bridle on Ways of Being | 5x15 - YouTube)... so there's lots to do.

We need not only to ask ourselves better questions, but think of better methods for addressing those questions. Some things don't need to be that complicated, and the seeds for new thinking are often in the past. Warren McCulloch's early work on neural networks (A heterarchy of values determined by the topology of nervous nets | SpringerLink), for example, contains these fascinating diagrams:

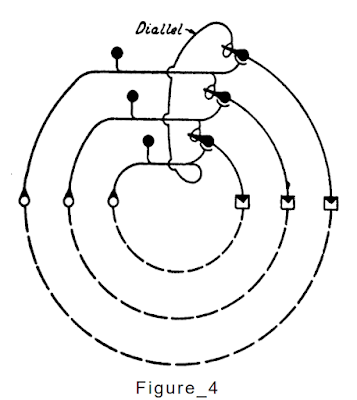

The above diagram explains McCulloch's notation: the continuous lines at the top are the nervous system, while the broken lines at the bottom are the environmental system. Receptors receive (transduce) signals from the environment, and effectors cause changes to the environment through behaviour of the organism (that's transduction too). There are two lines above representing (for example) two variables or categories of perception (perhaps "black" and "white"). But this diagram above does nothing: what goes in comes out.The diagram below is much more interesting. The feedback of each category is wired into every other category (rather like the Ashby homeostat), and this keeps the thing in flux. What does that mean for our values? Perhaps left to our own devices we would forever be shifting from one category to another. But in communication with other such systems, stabilities in the perceptual apparatus of many people will result in values which can be codified and assumed to be "fixed" (although what appears static is an epiphenomenon of a continuous process):

"The inquiry into the physiological substrate of knowledge is here until it is solved thoroughly, that is, until we have a satisfactory explanation of how we know what we know, stated in terms of the physics and chemistry, the anatomy and physiology, of the biological system"

No comments:

Post a Comment