Saturday, 30 July 2022

Scientific Economy and Artistic Technique

Tuesday, 26 July 2022

Prufrock's Soul

A university friend said to me the other day that she felt writing academic papers was not nourishing in the same way as more artistic things that she did (but did less since she spent more time writing papers). I agree, and this makes me want to know more about differences between the qualia of different creative activities. What is nourished when the soul is nourished? What might be the mechanism?

Spiritual nourishment is visceral. There is a sensation, perhaps somewhere near the solar plexus, which is activated with certain activities which might be considered to be nourishing. Personally, my solar plexus rarely responds when I am writing. I know this because as I write this, I cannot feel it: the activity is in my head, not my belly. When I think more about the specific feeling of "soul nourishment" then I will rehearse those things which produce it - gazing at a beautiful sunset, beautiful moments in music, water - both still and a flowing stream, a cathedral or grand library.

There is something primeval about these experiences: something timeless. In the evolutionary theory of John Torday, as biological entities, we are phenotypes seeking information to return us to an original evolutionary state. Sometimes the seeking can go wrong and we simply end up lost. When T.S. Eliot writes in the "Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock":

"I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas."

The ragged claws are the primal evolutionary state; Prufrock's weary, regretful, sexually repressed, empty-souled persona is the result of evolutionary accretions in search of a return to the simplicity of evolutionary origins which have only further obscured any deeper satisfaction. And Prufrock is lost. But the poem points to a kind of vector that connects primal origins to an empty life in search of meaning.

The point about this is that Eliot's soul was nourished in writing about a lost soul. The similarity to Dante is obvious. But what is it about Eliot's art which enables him to articulate this connection?

Great poets, artists and composers harness energy. John Galsworthy commented about art and energy that:

Art is that imaginative expression of human energy, which, through technical concretion of feeling and perception, tends to reconcile the individual with the universal, by exciting in him impersonal emotion. And the greatest Art is that which excites the greatest impersonal emotion in an hypothecated perfect human being.

(I'm grateful to Marie Ryberg for drawing my attention to Dewey's "Art as Experience" where he quotes this Galsworthy passage.)

Eliot's poem does this. And the writing of academic papers does not have this effect. The question, it seems, is about energy. He understood the energy vector that connects his art and technique to a deeper truth about the universe, and the plight of J. Alfred Prufrock.

Academic writing is rather deathly by comparison. The desire to explain away things which can't be explained, and conform to expectations of "proper referencing", "cogent arguments", "rigorous methods", etc, kills the soul. It might reward academics with promotion within an insane (and increasingly broken) system, but unless the work is truly ground-breaking, it amounts to little more than paraphrases of what has gone before. This is particularly true of education research.

When we do more deeply creative things, however, we engage with the energy that connects the scuttling claws with our present state. The regression connects us to where we come from, and where we are going. The are a number of hormonal and epigenetic factors which kick-in in the process. Moreover, the technique of creative work is very similar to what Galsworthy describes: a technical concretion of feeling and perception. The artist's challenge is to develop a technique whereby this can be managed.

The deep challenge with this is that, of course, education does not see itself in relation to primal origins and energy vectors! It sees itself in relation to the development of independent "selves" as economic units in the making. But primal origins are what connect us to each other. What we imagine as our independent "self" is merely an apparatus for collecting epigenetic information and eventually transferring it to a new zygote, which will grow to some new apparatus for collecting information.

Darwinian natural selection privileges the organism surviving in its environment, whereas the organism may merely be a vehicle for passing epigenetic information back to a zygote. It's ironic that Darwin's model probably had its origins in Darwin's schooling, while the establishment of the evolutionary model has reinforced an attitude to educational growth and development which has pushed creativity out in favour of STEM-related nonsense.

Saturday, 16 July 2022

Disentangling Entanglement in the Social Sciences

One of the most unfortunate aspects of increasing interest in topics like complexity and systems is the appropriation of scientific terminology to obfuscate the kinds of problems which the systems sciences were developed to enlighten. It's not exactly the same problem as Sokal (Fashionable Nonsense - Wikipedia) identified 20 years ago as a kind of intellectual scientific posturing - that, he argued, was at worst a kind of fraud, and at best, intellectual laziness. What we see now is more of the latter, but it exists in a dominant normativity where it's almost impossible to suggest that simply saying stuff is "complex" is to do no more than posit a blanket "explanatory principle" which explains away intellectual difficulties, rather than invites the question "how? so then what?".

Entanglement - as it has been used by Latour and others - is a case in point. Latour has positioned himself carefully here (see Bruno Latour, the Post-Truth Philosopher, Mounts a Defense of Science - The New York Times (nytimes.com) because he is aware of the problem (and as someone who began their career doing information theoretical analyses, he should know), but that hasn't stopped a sociomaterial industry (particularly in management science and education) growing up with long words and nothing much to say. Like all industries, it seeks to defend its position, which makes challenging it very difficult, and any practical educational progress even less likely.

In physics, entanglement refers to the specific state of affairs in quantum mechanics where non-local phenomena are causally connected in ways which cannot be explained by conventional (Newtonian, locality-based) physics. If there is a fundamental underpinning idea here, it is not so much the weird interconnections between what might be seen to be "separate" variables, but rather the distinction between local and non-local phenomena, and the ways in which the totality of the universe is conceived in relation to specific locally observable events. Talking about entanglement without at least considering it in the light of totality and non-locality is like talking about the reality of ghosts on a fairground ghost train.

Part of the problem is that we have no educational cosmology - no understanding of totality, or rather how education fits in a totality of the universe. This seems a grand and ambitious task - but if we deny that such a thing is possible, we then cannot defend allusions to science to help us address educational problems. This is why better educational thinkers are thinking about physics, education, technology and society together (this is good: Against democracy: for dialogue - Rupert Wegerif). James Bridle's new book "Ways of Being" is also better - containing a lot of good stuff about biology and cybernetics - although again, it's hard to see a coherent cosmology... (very interesting interview between him and Brian Eno here: Brian Eno and James Bridle on Ways of Being | 5x15 - YouTube)... so there's lots to do.

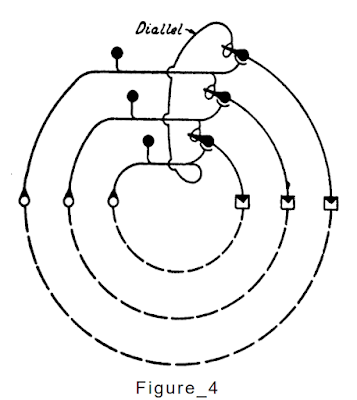

We need not only to ask ourselves better questions, but think of better methods for addressing those questions. Some things don't need to be that complicated, and the seeds for new thinking are often in the past. Warren McCulloch's early work on neural networks (A heterarchy of values determined by the topology of nervous nets | SpringerLink), for example, contains these fascinating diagrams:

The above diagram explains McCulloch's notation: the continuous lines at the top are the nervous system, while the broken lines at the bottom are the environmental system. Receptors receive (transduce) signals from the environment, and effectors cause changes to the environment through behaviour of the organism (that's transduction too). There are two lines above representing (for example) two variables or categories of perception (perhaps "black" and "white"). But this diagram above does nothing: what goes in comes out.The diagram below is much more interesting. The feedback of each category is wired into every other category (rather like the Ashby homeostat), and this keeps the thing in flux. What does that mean for our values? Perhaps left to our own devices we would forever be shifting from one category to another. But in communication with other such systems, stabilities in the perceptual apparatus of many people will result in values which can be codified and assumed to be "fixed" (although what appears static is an epiphenomenon of a continuous process):

"The inquiry into the physiological substrate of knowledge is here until it is solved thoroughly, that is, until we have a satisfactory explanation of how we know what we know, stated in terms of the physics and chemistry, the anatomy and physiology, of the biological system"

Tuesday, 5 July 2022

Cells and Sociomateriality

The sociomaterial gaze looks upon the world as a set of interconnections. Running through the "wires" of this web is the agency of individual entities - humans (obviously) and (more controversially) objects and technologies constituting organisational structures, power relations, roles, etc. To deal with the complexity of this presentation of the world, sociomaterialists evoke ideas from quantum mechanics like "entanglement" and (occasionally) "superposition" to explain the complex interactions between the components, looking to science (as represented, for example, by the interpretation of Bohr by Karen Barad) to supply sufficient doubt over the ability to be more precise about what is actually going on. If I was being unkind, I would say the end result has been a lot of academic papers with long words which mystify more than they enlighten. Even critiquing it seems to invoke complex vocabulary: "heterogeneous dimensions are homogenized in a pan-semiosis" (Hagendijk, 1996 - see https://www.leydesdorff.net/mjohnson.htm) - well, yes.

Gazing at the world's complexity and trying to explain it by purely focusing of manifest phenomena is like trying to explain the universe but ignoring its expansion. The synchronic (structural) dimension alone will not suffice. History - the diachronic dimension - is critical to get a perspective which is more scientifically defensible. It is a profound change in perspective: the diachronic dimension enables us to see the world in 3D. This means that we have to draw away from looking at the relation between objects/technologies and people (for example), and instead focus on life itself - to understand not only life's characteristics, but the mechanisms behind its creation of the material environment with which sociomateriality is so fascinated. This is a project connecting Lamarck, Bateson, Schrodinger and Bohm with recent work ranging from astrobiology, cellular evolution and epigenetics.

I want to explain why this diachronic perspective is a much more powerful way of looking at education, technology and human life.

Every one of my cells has a history. Not just the history of where it began in me - which was in one of the three "germ layers" of the zygote that eventually grew into baby me - but a deeper history of how each of the (roughly) 200 different cells types emerging from the zygote acquired their individual structures and properties. Each of them has a history much older than me. Each of them acquired different components (organelles) which we now see as a process of absorption of externally existing components in the environment: endosymbiosis. Cellular endosymbiosis occurred in response to environmental stress. Early cells had to reorganise their structures and functions in order to maintain:

- homeostasis within the cell boundary

- balance with the external environment

- energy acquisition from the environment