My recent posts have been concerned with the nature and process of explanation. This fascinates me because not only is it central to understanding learning, but also in understanding the broader ways in which human beings organise themselves in institutions, businesses, families, and so on. Explanation is the thing that is continually going-on within what can appear to be 'self organising' social systems.

I'm interested in understanding these processes and trying to formalise their dynamics. There are many paradoxes about even wanting to do this: what I am producing is, after all, an explanation! But at the same time, I think there is value in working towards a more formalised way of thinking. Here, it is Nigel Howard's work on the 'Paradoxes of Rationality' which is interesting me most. Howard's 'paradox' is essentially a critical appreciation of game theory, where the rational assumptions of Von Neumann's game theory are followed to the their logical conclusions, and the rational behaviour which is supposed to underpin the playing of games (with their assumed ordinal pay-offs) is undermined by a careful examining of meta-strategies, coalitions, and the meta-games that are played with meta-strategies. A different kind of mathematics emerges, and as with all mathematics, this begins to reveal the limits of logic and knowledge. There's a paper or two in that, but I'll begin to explore it here shortly.

But before I dive into this, I'm being dragged-back (as I often do) to thinking 'how does this work for music?'. Because, whilst I am thinking about new mathematical formalisms for thinking about how things like the Viable System Model might work (one of the 'games' that I believe can be accounted for by Howard's work), music presents different kinds of problems, which may or may not fit the game metaphor.

Kant characterised artistic experience as a kind of cognitive 'game'. He says in the Critique of Judgement that:

Here I think it is important to take a step back from these questions and ask why they are asked. What I recognise myself as wanting to do is 'explain music'. Kant and Gadamer have provided a tantalising glimpse of an explanation... but how to make it more concrete, less "arm-wavy"? But then, why am I not satisfied with this explanation on its own?

There seems to be a connection between the desire to explain phenomena like music and the desire to understand processes of human social organisation, economics, business management, etc. The problem lies in the poverty of the explanations for economics and business in the face of the raw and profound experience provided by music.

Recently I've been struck by the power of some explanatory frameworks to try to bridge the gap between the deep human sensual experiences and the prosaic organisational concerns. In fact, there is plenty of slightly 'wacky' literature out there to try to do this: for example, Neuro-Linguistic Programming, Beck's 'Spiral Dynamics' or Jungian personality types; I suspect the VSM also fits into this category.

These are relatively new-fangled explanations. But they bear many similarities to more ancient explanatory frameworks. What about Tarot, Astrology or the I Ching? Or, for that matter, the allegories of the major religions and myths? Notwithstanding the content of these explanations, their explanatory function is very similar. They consist of a series of distinctions with an explanatory framework which connects those distinctions together (or rather, manipulates a probability distribution of certain distinctions following on 'logically' from others).

I wonder if it is this pattern of weaving distinctions together that characterises the process of explanation. However music is explained, the explanation will take a form of "there are these elements, and because there are these elements, these events are more or less likely". In terms of explaining music, the words which we explain things will be uttered in social company: there will need to be agreement. Here, the game of explaining music is as social as the game of explaining business organisation. I suspect it's a game of 'maintaining coalitions'. But the agreement that the coalition will be built on will be based on something more profound, sensual and pre-linguistic. My suspicion is that agreement about these things depends on the recognition of shared absence.

Deep down, music is its own explanation. Like Isadora Duncan famously remarked about her dancing: "No, I can't explain the dance to you; if I could tell you what it meant, there would be no point in dancing it." Music (like dance) explains. Or perhaps we might say, music unfolds. The game that our senses play with the art object that Kant and Gadamer allude to is related to the game that we play with each other when we explain our understanding. It is an unfolding of possibilities. Our verbal explanations might well serve our maintenance of coalitions, attachments to others, etc; the unfolding of music, or the self-explaining of music may also serve our maintenance of coalitions and attachments to others, but through affording us a deeper relationship with ourselves. In the realm of the senses we re-adjust and reform our equipment for social life.

There's one more thing to add here. Because it is, I think, a mistake to see our sensory equipment as some sort of inner-processing mechanism. It is instead the very process of sensual play where we are one of the players in the world of the senses. The game reveals what lies beyond the game. Music, as with the other arts, helps us to perceive what we cannot know; it's action is negative. As it brings the unknowable into sharper relief, so the grounds for recognition, love and agreement can be established. The extent to which this negativity is fundamental to explanation generally is the central question which lies behind any attempt to formalise explanation (and any good formalism will itself reveal what cannot be known).

So I have one question at the end of all this, which may appear a little abstruse: is the identification of shared absence the deepest meta-strategy which leads to the broadest and strongest coalition?

I'm interested in understanding these processes and trying to formalise their dynamics. There are many paradoxes about even wanting to do this: what I am producing is, after all, an explanation! But at the same time, I think there is value in working towards a more formalised way of thinking. Here, it is Nigel Howard's work on the 'Paradoxes of Rationality' which is interesting me most. Howard's 'paradox' is essentially a critical appreciation of game theory, where the rational assumptions of Von Neumann's game theory are followed to the their logical conclusions, and the rational behaviour which is supposed to underpin the playing of games (with their assumed ordinal pay-offs) is undermined by a careful examining of meta-strategies, coalitions, and the meta-games that are played with meta-strategies. A different kind of mathematics emerges, and as with all mathematics, this begins to reveal the limits of logic and knowledge. There's a paper or two in that, but I'll begin to explore it here shortly.

But before I dive into this, I'm being dragged-back (as I often do) to thinking 'how does this work for music?'. Because, whilst I am thinking about new mathematical formalisms for thinking about how things like the Viable System Model might work (one of the 'games' that I believe can be accounted for by Howard's work), music presents different kinds of problems, which may or may not fit the game metaphor.

Kant characterised artistic experience as a kind of cognitive 'game'. He says in the Critique of Judgement that:

"The cognitive powers, which are involved by this representation, are here in free play, because no definite concept limits them to a particular rule of cognition. Hence, the state of mind in this representation must be a feeling of the free play of the representative powers in a given representation with reference to a cognition in general."Kant's ideas about play also form an important element in the aesthetic theory of Gadamer. But if what is happening in aesthetic experience is 'play', what's the game? is there one? can it be characterised?

Here I think it is important to take a step back from these questions and ask why they are asked. What I recognise myself as wanting to do is 'explain music'. Kant and Gadamer have provided a tantalising glimpse of an explanation... but how to make it more concrete, less "arm-wavy"? But then, why am I not satisfied with this explanation on its own?

There seems to be a connection between the desire to explain phenomena like music and the desire to understand processes of human social organisation, economics, business management, etc. The problem lies in the poverty of the explanations for economics and business in the face of the raw and profound experience provided by music.

Recently I've been struck by the power of some explanatory frameworks to try to bridge the gap between the deep human sensual experiences and the prosaic organisational concerns. In fact, there is plenty of slightly 'wacky' literature out there to try to do this: for example, Neuro-Linguistic Programming, Beck's 'Spiral Dynamics' or Jungian personality types; I suspect the VSM also fits into this category.

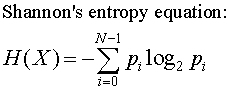

These are relatively new-fangled explanations. But they bear many similarities to more ancient explanatory frameworks. What about Tarot, Astrology or the I Ching? Or, for that matter, the allegories of the major religions and myths? Notwithstanding the content of these explanations, their explanatory function is very similar. They consist of a series of distinctions with an explanatory framework which connects those distinctions together (or rather, manipulates a probability distribution of certain distinctions following on 'logically' from others).

I wonder if it is this pattern of weaving distinctions together that characterises the process of explanation. However music is explained, the explanation will take a form of "there are these elements, and because there are these elements, these events are more or less likely". In terms of explaining music, the words which we explain things will be uttered in social company: there will need to be agreement. Here, the game of explaining music is as social as the game of explaining business organisation. I suspect it's a game of 'maintaining coalitions'. But the agreement that the coalition will be built on will be based on something more profound, sensual and pre-linguistic. My suspicion is that agreement about these things depends on the recognition of shared absence.

Deep down, music is its own explanation. Like Isadora Duncan famously remarked about her dancing: "No, I can't explain the dance to you; if I could tell you what it meant, there would be no point in dancing it." Music (like dance) explains. Or perhaps we might say, music unfolds. The game that our senses play with the art object that Kant and Gadamer allude to is related to the game that we play with each other when we explain our understanding. It is an unfolding of possibilities. Our verbal explanations might well serve our maintenance of coalitions, attachments to others, etc; the unfolding of music, or the self-explaining of music may also serve our maintenance of coalitions and attachments to others, but through affording us a deeper relationship with ourselves. In the realm of the senses we re-adjust and reform our equipment for social life.

There's one more thing to add here. Because it is, I think, a mistake to see our sensory equipment as some sort of inner-processing mechanism. It is instead the very process of sensual play where we are one of the players in the world of the senses. The game reveals what lies beyond the game. Music, as with the other arts, helps us to perceive what we cannot know; it's action is negative. As it brings the unknowable into sharper relief, so the grounds for recognition, love and agreement can be established. The extent to which this negativity is fundamental to explanation generally is the central question which lies behind any attempt to formalise explanation (and any good formalism will itself reveal what cannot be known).

So I have one question at the end of all this, which may appear a little abstruse: is the identification of shared absence the deepest meta-strategy which leads to the broadest and strongest coalition?